Each year, collectors enjoy the variety of mineral competitions at the Tucson Mineral and Gem Show™, where multiple awards are given out for best minerals, themes, displays, and more. Some of the most popular are listed here, as explained at the TGMS website with special additions by Lauren Megaw and Les Presmyk.

There are several special trophies awarded to competitive exhibits at the annual Tucson Gem & Mineral Show. The first is the Desautels, honoring the long-time curator of minerals at the Smithsonian. This award is for the best case of minerals entered in that competition. The second is the Lidstrom trophy, acknowledging a long-time dealer in the Tucson Show. It goes to the best single specimen, as designated by the exhibitor, contained within a competitive exhibit. The third is the Bideaux Trophy, awarded to the Best Arizona specimen in that competition. Dick Bideaux was a native Tucsonan and one of Arizona’s top mineralogists. These are in addition to the trophies awarded to the best case in each of the exhibitor classes and for the Best of Theme categories. Information for the Tucson Show competition and all of these trophies can be found at www.tgms.org/show.

There is one more special trophy, the Romero Trophy, that is awarded to the best Mexican specimen in the show. This award honors the memory of Dr. Miguel Romero, often credited with saving and preserving Mexico’s minerals and mineral heritage. The trophy winning specimen is selected by a judging team of three of his friends and the trophy is presented along with all of the competitive trophies mentioned above at the Saturday night banquet and awards ceremony.

WALT LIDSTROM MEMORIAL TROPHY

[box]To honor the memory of Walt Lidstrom, noted mineral dealer and collector, TGMS, along with his family, present a trophy for the outstanding single mineral specimen which is part of a competitive exhibit.[/box]

Walt Lidstrom (1920-1976) was a game-changing mineral dealer. Originally a rancher from Oregon, Lidstrom began collecting Oregon plumes agates in 1939, by 1960 he had amassed an impressive amount of top-notch slab material and made his way to his first mineral show. As his business, Lidstrom’s, began to grow he transitioned to fine crystallized mineral specimens. He used both his self-taught knowledge and a keen eye for spectacular specimens to make himself a leading expert in the field. Lidstrom is commonly credited with changing the mineral dealing business, from ma-and-pop shops, to a reputable professional business. He thrived on mineral competition and enjoyed watching the business grow. Lidstrom would buy from rock-hounds, college kids and other professionals. During his tenure as a dealer, he garnered a reputation for honesty, spectacular sense of aesthetics, depth of knowledge and good humor. Lidstom died just days after the 1976 Tucson Gem and Mineral show wrapped up, having attended to see his friends one last time.

It is fitting that the Lidstrom award, established by his family in 1978 and continued by the Tucson Show Committee, would require competitive cases in its award. The award is given to the single best specimen in competition, as selected by the competitor. This last bit is an important caveat, because the award both honors a fabulous specimen, but also the competitor’s “eye” for selecting the best specimen they own. Many a Lidstrom has been lost due to a competitor selecting the wrong specimen. The selection is entirely subjective. It is awarded to the best piece in the eyes of the three quality judges, and to win Lidstrom a piece must be exceptional for its species as well as having great aesthetics.

Notable winners of the Lidstrom mineral competitions include: Will Larson, Paula Presmyk, Gene Meiran, Peter Megaw, Ralph Clark, Gail and Jim Spann, Barry Kitt and Lauren Megaw.

[caption id="attachment_4747" align="aligncenter" width="300"] Exhibit case in the Tucson Gem and Mineral Shows mineral competition.[/caption]

Exhibit case in the Tucson Gem and Mineral Shows mineral competition.[/caption]

PAUL DESAUTELS MEMORIAL TROPHY

[box]To honor the memory of Paul Desautels, curator, collector and connoisseur of fine minerals, TGMS presents a trophy for the individual display of the finest crystallized mineral specimens entered in this competition.[/box]

Paul Ernest Desautels (1920-1991), an eminent curator, began his mineralogical endeavor at 14 in Philadelphia where he grew up. It was there collecting primarily as a micro-mounter that he would exchange specimens, knowledge and tales with other collectors such as Neal Yedlin, a micro-mounter for whom another award is given. Desautels would go on to receive both a B.S. and a M.S. in Chemistry from the University of Pennsylvania, and fight in World War II between his two degrees. After school he went on to become a chemistry teacher, though Desautels would occasionally teach courses in mineralogy, gemology and crystallography.

In 1957, Desautels began his renowned career as Curator of Gems and Minerals in the Department of Mineral Sciences of the U.S. National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian Institution) in Washington, D.C., a position he would hold for 25 years. During his time at the Smithsonian, Desautels pursued acquisition with zeal, solidifying the Smithsonian as one of the greatest mineral collections in the world. The Carl Bosch collection, 25,000 fine mineral specimens acquired by the Smithsonian in 1970, was probably the greatest acquisition by the institution in the 20th century. He was also an incredibly influential figure in the minerals community, writing voluminous correspondence, a column on museums in the Mineralogical Record, a series of popular books on mineral and gem collecting, delivering hundreds of public lectures, and his relationships with a tremendous number of curators, collectors and dealers in the world.

It was through this influence that Desautels brought connoisseurship of minerals to the forefront of collecting, and helped usher in a new age in collecting. He also worked as an acquisition consultant for Texas oil millionaire Perkins Sams, whose collection was eventually acquired by the Houston Museum of Natural Science. Over his lifetime Desautels amassed many honors including:reception of the American Federation of Mineralogical Society’s Scholarship Award in 1967, induction in the Micromounter’s Hall of Fame in 1981, reception of the Carnegie Mineralogical Award in 1991, and reception of the Smithsonian Director’s Medal for outstanding service to the National Museum of Natural History. He was a Fellow of the Mineralogical Society of America, and founded the Baltimore Mineral Society. And so, when the McDole Trophy was retired, Desautels’ name was placed on the trophy representing the single best case in each year's mineral competition. Desautels died on July 5, 1991.

Notable winners of the Desautel Award include: Gene and Roz Meiran, Paula Presmyk, Alex and Laura Schauss, Peter Megaw, Jim and Gail Spann, Barry Kitt and Lauren Megaw.

BEST OF SPECIES OR THEME COMPETITION

[box]Each year the TGMS Show Committee selects a mineral species or a mineral theme for special mineral competition. Awards are given for the best specimen in each of five size categories, one award for lapidary/jewelry, one award for a self-collected specimen, and if appropriate, one award is given for the best Arizona specimen of the named species (please see special rules and listing of species).[/box]

RICHARD BIDEAUX MEMORIAL TROPHY

[box]To honor the memory of Richard Bideaux, collector, Arizona mineralogist and connoisseur of fine minerals, TGMS presents a trophy for the finest crystallized Arizona mineral specimen entered in this mineral competition.[/box]

Richard Bideaux was born on March 28, 1935 in Tucson, Arizona. As fate would have it, Bideaux became interested in minerals and began collecting in the local area with his father George. Later on he and his collecting partner Richard “Dick” Jones collected many notable Arizona specimens including wulfenite from both the Defiance and Glove mines. He stayed in Tucson for college attending the University of Arizona, and graduating in 1959 with a Bachelors degree in Geological Engineering. He was then drafted into the Army, and found his way to a base in New Jersey. While on the east coast, when he wasn’t training in computer programming, Bideaux visited mineral museums and befriended mineral collectors and dealers.

Upon departure from the service, Bideaux worked for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. And once again the affable Bideaux became acquainted with many West Coast mineral collectors and dealers when he wasn’t working on the Lunar Survey. Bideaux then went back east to Harvard, where in 1968 he graduated with a master’s degree in mineralogical science. He then returned to his hometown and founded Computing Associates, Inc, a company working on computer applications in geology and mine engineering. In 1978 the University of Arizona conferred upon him the professional degree of Geological Engineer for his achievements in computer science.

Meanwhile he also brought together Arthur Montgomery and John White, who founded the Mineralogical Record in 1970. Bideaux’s column “The Collector” appeared in early Mineralogical Records as well as his incredible article on Tiger, Arizona. Along with Sid Williams and mineralogy professor John Anthony, Richard wrote Mineralogy of Arizona in 1977. Two years later, following the death of his father, Richard took over Bideaux Minerals, and it was through this outlet that fantastic minerals specimens found their way into private collections and museums around the world. In 1980, Bideaux along with John Anthony, Ken Bladh, and Monte Nichols took on the six-volume Handbook of Mineralogy, one of the most important books of mineralogical reference. He was a founder and first president of Friends of Mineralogy, a life fellow of the Mineralogical Society of America and a member of the Arizona Geological Society. Bideaux was a key member in building the collections of the University of Arizona Mineralogical Museum as well. And on top of all of that he was a major component of the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show for 50 years helping to turn it into the international phenom it is today.

Richard had a mineral, Bideauxite, named after him by Sid Williams in 1970 as well. But above all, Bideaux was a collector. He collected throughout his life, a large part of which was self-collecting, and although he sold the majority of his collection in 1985 his love for collecting a minerals remained till the end of his days in 2004. Bideaux didn’t just collect minerals, however, he also garnered a label collection of over 3,500 examples which were donated to the Mineralogical Record Library and forms the backbone of the Mineralogical Record Label Archive. Richard Bideaux inspired many mineral collectors, not only to collect and appreciate the minerals, but also to take a genuine scientific interest in better understanding the specimens that we all love to collect.

Notable Winners: Steve Maslansky, Irv Brown, Dick Morris, and Les Presmyk

NEAL YEDLIN MEMORIAL MICROMOUNT TROPHY

[box]To honor the memory of Neal Yedlin, noted micromounter and mineral collector, TGMS presents a trophy for the individual display of micromounts achieving the highest score in the Masters Micromount Division.[/box]

MIGUEL ROMERO MEXICAN MINERAL AWARD

The Romero award goes to the single best Mexican mineral on the show floor. This means that any mineral specimen from Mexico in a case at the show - competitive, exhibition, or institutional - has the opportunity to win the Romero Award. The specimen is selected by a jury of Mexican mineral specialists who look through all the exhibits at the show and confer on which specimen should receive the award.

Notable Winners: Jim and Gail Spann, Kerith Graeber, Peter Megaw, and Roz Pellman

Want to learn more about competing in the Tucson Show? Get in touch to ask us about curating your collection.

To learn about one of our favorite young collectors and her experience competing in a variety of the TGMS mineral competition categories, visit "Growing Up Rocks - Lauren Megaw's Mineral Story."

Lauren also wrote a note about showmanship and how to prepare a display for the annual Tucson Gem and Mineral Show mineral competition. Don't miss reading her story!

Amethyst from Vera Cruz, Mexico. Joe Budd Photo, Jeff Starr Collection[/caption]

Amethyst from Vera Cruz, Mexico. Joe Budd Photo, Jeff Starr Collection[/caption] Amber found in north Poland with insect inside, auctioned on MineralAuctions.com[/caption]

Amber found in north Poland with insect inside, auctioned on MineralAuctions.com[/caption] Bumblebee Jasper from Indonesia auctioned on MineralAuctions.com[/caption]

Bumblebee Jasper from Indonesia auctioned on MineralAuctions.com[/caption]

Amethyst Geodes like this one are a hot trend in home decor and provide inspiration for the popular geode cake trend.[/caption]

Amethyst Geodes like this one are a hot trend in home decor and provide inspiration for the popular geode cake trend.[/caption]

The gemstone at the front of George V's Imperial State Crown. G. Younghusband; C. Davenport (1919). The Crown Jewels of England. London: Cassell & Co. p. 6.[/caption]

The gemstone at the front of George V's Imperial State Crown. G. Younghusband; C. Davenport (1919). The Crown Jewels of England. London: Cassell & Co. p. 6.[/caption] 1879 Morgan Dollar Coin[/caption]

1879 Morgan Dollar Coin[/caption]

The Dehli Purple sapphire - revealed later to be an amethyst. Source: Natural History Museum (London)[/caption]

The Dehli Purple sapphire - revealed later to be an amethyst. Source: Natural History Museum (London)[/caption]

Lauren Megaw as a child posing in front of her award-winning Tucson Show mineral display[/caption]

Lauren Megaw as a child posing in front of her award-winning Tucson Show mineral display[/caption] The color of the liners should be become essentially invisible allowing the specimens to do all the talking. Here is the tricky part: finding a fabric in a color that allows red, blue, and green to pop without losing either your dark or clear specimens. I find that either a light beige or a grey works great. As you compete more, fiddling with the color is a fun way to optimize your display. Be careful with getting too light or too dark with your liner colors. I suggest going to the fabric store with a clear quartz crystal and a dark mineral (nothing fancy), to make sure either doesn’t completely disappear. Also remember that the competitive displays use incandescent bulbs, and fabric stores usually have fluorescent lighting making the fabric appear more blue then it will be on the show floor.

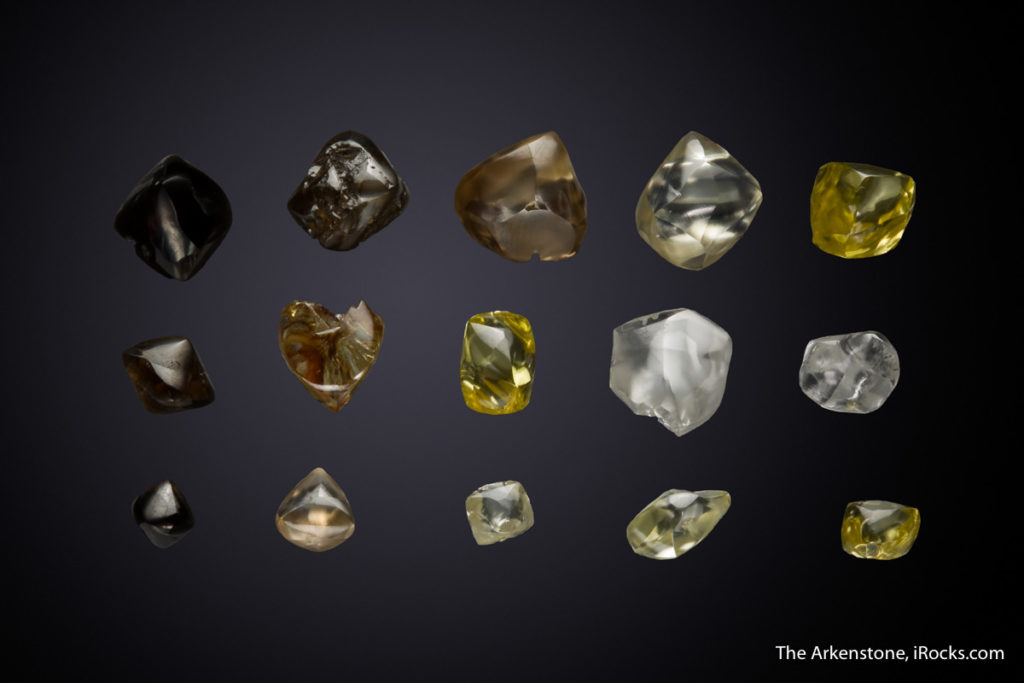

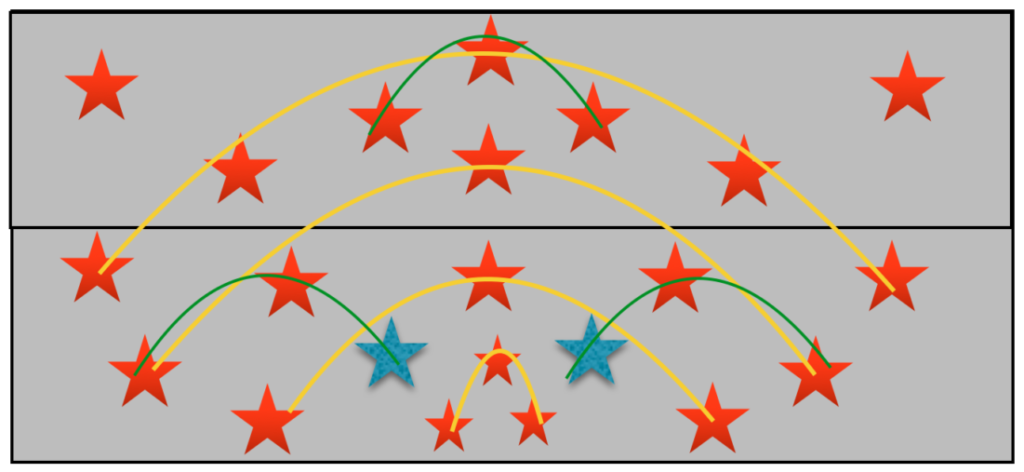

The color of the liners should be become essentially invisible allowing the specimens to do all the talking. Here is the tricky part: finding a fabric in a color that allows red, blue, and green to pop without losing either your dark or clear specimens. I find that either a light beige or a grey works great. As you compete more, fiddling with the color is a fun way to optimize your display. Be careful with getting too light or too dark with your liner colors. I suggest going to the fabric store with a clear quartz crystal and a dark mineral (nothing fancy), to make sure either doesn’t completely disappear. Also remember that the competitive displays use incandescent bulbs, and fabric stores usually have fluorescent lighting making the fabric appear more blue then it will be on the show floor. Pods (represented in Fig. 1 by green arcs) allow for the competitor to highlight pieces through contrast. Each specimen in a pod should complement each other, while a rainbow should allow your eyes to flow across them.[/caption]

Pods (represented in Fig. 1 by green arcs) allow for the competitor to highlight pieces through contrast. Each specimen in a pod should complement each other, while a rainbow should allow your eyes to flow across them.[/caption]

Old Brazilianites from the 1930s-1940s are still rare mineral superstars![/caption]

Old Brazilianites from the 1930s-1940s are still rare mineral superstars![/caption]

Exhibit case in the Tucson Gem and Mineral Shows mineral competition.[/caption]

Exhibit case in the Tucson Gem and Mineral Shows mineral competition.[/caption]