Little Wonders: Connoisseur Thumbnails in the Contemporary Collector Market

Written by Dr. Jim Houran, Jim Bleess, and Dr. Alex Schauss.

Adapted with permission for publication on iRocks.com

Introduction

Mineral collectors generally differentiate six specimen sizes, starting with the smallest, termed micromounts, followed by thumbnails, toenails, miniatures, small cabinet and ending with large cabinet or museum-size pieces. In some cultures massive size is equated to quality, but collectors past and present have more often observed that bigger is not always better. Rather, the opposite is usually the reality with minerals. Large, perfect crystals are uncommon for several reasons. Most notably, bigger crystals require more space to grow, which often is unavailable. Even with open space, the diffusion rates are typically such that it is ‘easier’ to nucleate a new crystal than for ions to migrate to the surface of an already growing crystal, encouraging the growth of more crystals rather than larger ones. Large, pristine crystals form only in environments allowing both ample space and high diffusion rates, such as pegmatites. Therefore, smaller crystals offer the highest degree of perfection and for this reason they have historically been very collectible.

In particular, Wendell Wilson and James Houran (2012) documented the long but somewhat quiet history and development of thumbnail collecting as a specialization. Thumbnails are specimens that can be oriented to fit within an imaginary 2.5 cm (1-inch) cube. In formal exhibit competition the unspoken amendment to this rule is that specimens should be oriented aesthetically within this space. Thumbnail specimens – for private collection or public competition – typically measure over ½ × ½ inch but generally not much larger than 1 × 1 inches and are considered to be the smallest size that can be appreciated without optical magnification.

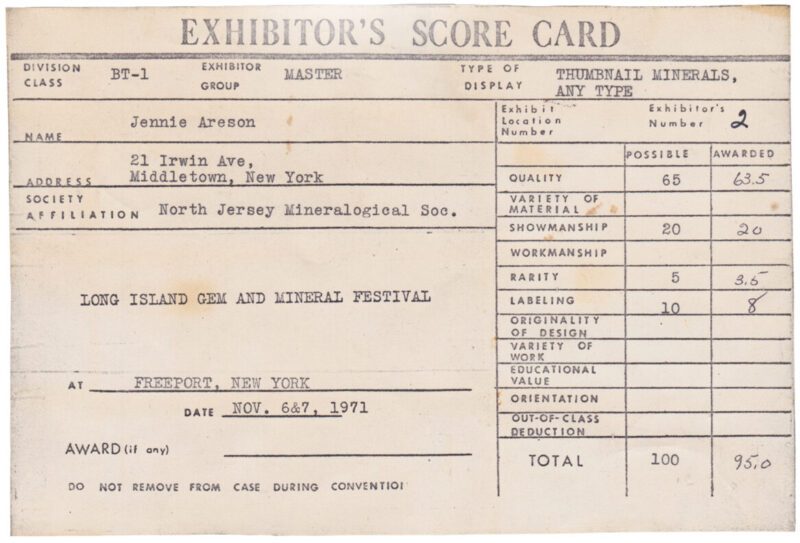

This makes thumbnails ideal for collecting, study and display. Prominent USA dealers and collectors such as Jim and Dawn Minette, Willard “Perky” Perkin (1907-1991), after whom the standard Perky Box is named, and others advanced the collecting of specific suites of minerals deemed “competitive thumbnails sizes, by the 1970s. Although it seems that “collector-dealers” started the trend to competitive thumbnail collecting, it was not long before “collector-collectors” got in on it as well. A well known example from the East Coast circuit is the collection of Jennie Areson of New York

An aside on Perky, courtesy of (Wendell Wilson’s) biography archive on the Mineralogical Record Site “Perkin was one of the first dealers to specialize in thumbnail-size specimens, and he had a talent for aesthetically trimming and mounting them. He built a fine personal mineral collection of high-quality cabinet-size and smaller specimens which he placed in drawers and on glass shelves in big glass-fronted display cases lining the walls of a small garage in his Burbank home. He also developed a strong interest in micromounting.” In the early 1956-1959 he worked for three years for mineral dealer George Burnham (“Burminco”) (q.v.) in Monrovia, California. While working in Burnham’s shop, Perkin was shown a small, cubical, black plastic box by a traveling salesman. It inspired the invention of what became known as the “perky” box, a 1.25-inch box for thumbnail specimens, which Perkin had manufactured and which he began selling to other collectors. When the number of orders coming in became overwhelming he sold the box business to someone else, but the name “perky box” stuck. In 1971 tragedy struck in the form of the Sylmar earthquake, which shattered the glass cases and shelves in his garage; the beautiful specimens crashed to the bottom of the cases together and out onto the concrete floor amid piles of broken glass. Perkin appeared to take the loss with good grace, but much of his enthusiasm for collecting minerals had died. Soon he began selling off the surviving specimens from the drawers, retaining only his thumbnails and micromounts.”

Although traditionally most popular in the United States, thumbnail collecting is an important and quickly growing segment of the mineral hobby due to several factors working in tandem, for instance, generally lower prices than popular hand-size specimens, easier handling and storage requirements and of course, the higher tendency for crystal perfection. Numerous mineral species also are known only in smaller sizes, meaning that some unique thumbnails may even qualify for a coveted “world’s best” designation. Top pieces exemplify the quality and importance small specimens can achieve when there is a balance of aesthetics, scientific relevance and historical importance. This is why many major collections have included thumbnails even though it may not have been a deliberate intention. Or, collectors who amassed large collections in the 1960s-1980s later separated out thumbnails into discrete suites once they went down that road by love of the minerals anyhow. A prime example is John Barlow, who had 5000 larger pieces and loved all sizes, yet eventually had separated out his thumbnails into a separate display collection with separate numbering. He later sold them to Rob Lavinsky apart from the sale of the main part of the Barlow Collection in 1998, and they remain in circulation today, recognizable by his own custom special display bases that fit his custom cabinets for thumbnails designed to make them “show off” amongst larger pieces.

Thumbnail collecting is a flexible and egalitarian specialty, open to beginning and advanced collectors who want inexpensive yet highly diverse specimens that require minimal storage space. That said, top-quality thumbnails have received a resurgence of interest and market value. This article reviews a confluence of three forces that have arguably helped to produce this heightened interest in fine thumbnails or what Thomas Moore, Mineralogical Record editor, aptly termed “connoisseur thumbnails” (Mineralogical Record, 33, p. 183).

The Rise of ‘Connoisseur’ Collecting

Interest in connoisseur thumbnails has been in step with an increased interest in fine specimens in general. To be sure, mineral collecting as a scientific, social and aesthetic endeavor as it is understood now is a relatively recent development that has been inextricably linked with the notion of connoisseurship (Cooper, 2010; Wilson, 1994). As Cooper (2010) noted, “With the rise, during the 17th century, of a scientific elite and a corresponding development of science as a gentlemanly pursuit, mineral specimens, along with all other productions of the natural world, came to be esteemed not only as tools with which to grasp the fundamental truths of nature, or as guides to hidden, exploitable wealth, but, increasingly, as objects desirable in their own right…’” (emphasis added, p. 5).

However, this holistic perspective has become increasingly diluted in modern times. Looking honestly at the collecting community today many hobbyists insist on differentiating two types of collectors, put simply as ‘purists’ and ‘elitists.’ These categories have been framed and discussed in different ways – for example, those who field-collect versus purchase (‘silver pick’) specimens, those who seek representative examples versus ‘trophy’ (elite quality) specimens, and those who advocate mineral science versus mineral art. In other words, purists equate connoisseurship with knowledge of the scientific aspects of specimens, whereas elitists are assumed to regard connoisseurship as rooted in understanding the aesthetic aspects of specimens. A cursory review of various online discussion boards like Mindat.org and the Friends of Mineralogy Forum (FMF) at Fabre Minerals reveals these perceptions to be quite strong and sometimes downright contentious when it comes to ‘purists’ commenting on connoisseur or ‘elite’ collecting, and sometimes vice versa.

The perceived distinction perhaps boils down to competing definitions of specimen significance, and by extension, a philosophy about the ‘correct’ approach to mineral collecting. Most collectors publicly agree that there is no singular, proper way to collect, except perhaps encouraging individuals to “collect what you like.” Yet in the same breath most will also concur with the seemingly contradictory but well-cited piece of advice to “buy the best you can afford.” In one scenario specimen quality is not a prerequisite, but in the other it is. Connoisseur collecting takes the latter advice one step further by motivating individuals to “buy the best there is.” This stringent focus on quality (significance combined with aesthetics) is actually nothing new. Charles Henry Pennypacker (1845-1911), collector, part-time dealer and frequent contributor to The Mineral Collector, levied harsh criticism at the hobby even in its early days. He asserted that a mineral collection is a representation of the collector, and as such, inexpensive specimens and bragging about “good deals you got on your specimens” rather than striving for the best, means that both you and your collection were an embarrassment (Lininger, 1993, p. 9). Of course, the collecting is personal and this is a spectrum, that also depends on the desire (and financing) of the collector. Luckily, Thumbnails in particular among other mineral classes, lend themselves to appealing to players of all means.

Of course, price is neither a synonym nor guarantee of quality. The same is true for the marketing claims of mineral dealers. Jolyon Ralph (2013) of Mindat argued that, “Phrases such as ‘world-class’, ‘museum quality,’ ‘exceptional,’ ‘unique’ or ‘ikon’ are meaningless marketing adjectives. Just ignore them, and I wouldn’t do them any service by promoting the use of them in a club magazine.” There is some truth to this observation; published authorities have rightfully cautioned that a mineral evaluation is only as meaningful as the knowledge and experience of the person making it. But the basic assertion that such descriptors per se are meaningless hyperbole is not shared by connoisseur-level collectors, since quality is not a purely subjective concept.

Many knowledgeable collectors, dealers and journal editors alike have outlined a generally agreed upon set of core attributes of connoisseur specimens (e.g., Bancroft, 1984; Wilson, 1990; Wilson, Bartsch & Mauthner, 2004; Smale, 2006; Halpern, 2005; Thompson, 2007; Currier, 2009; Wilson & Houran, 2012; Houran, 2013; Lavinsky & Moore, 2013). These sources effectively explain specimen aesthetics, i.e., the visual, sculptural qualities that are most desirable to Western collectors. Plus, the ongoing record of mineral finds in the academic literature regularly informs collectors about what constitutes the highest development of a species to date in terms of color, form and condition, i.e., specimen significance. Contrary to the apparent prevalence of ‘purist’ attitudes in its membership, Mindat also implicitly incorporates an ‘elitist’ perspective with its ongoing “Best Minerals” project. This initiative aims to document significant specimens by species and locality. There is therefore unquestionably a hierarchy of quality, with aesthetics and significance defining the level synonymous with ‘exceptional,’ ‘world-class’ or ‘connoisseur’ specimens.

The connoisseur philosophy is visible in the hobby in many other ways. One of the most obvious, pervasive and influential examples is the multitude of well-produced periodicals and books that outline the criteria for specimen quality, discuss the major localities where the best examples are found and present illustrative specimens. Thompson (2007) and Currier (2008) identified the best classic and current texts on minerals that serve as excellent primers. Plus, the many outstanding Mineralogical Record supplements, extraLapis issues and the monographs from Lithographie all tend to show the finest specimens from top collectors. This literature suggests that the number of connoisseur collectors is healthy, even though they may not constitute the majority in the mineral hobby.

The editorial priority in illustrating only the best specimens in periodicals has detractors who complain the practice is elitist rather than scientific. Speaking to this issue, Mineralogical Record editor-in-chief Wendell Wilson countered that the practice was unquestionably educational for readers (Praszkier, 2012, p. 16; cf. Wilson, 2013). He reasoned that the best specimens show the fullest development of the various features and qualities of a species, which collectors can then extrapolate downward to lesser specimens. On the other hand, no one can look at lesser specimens and know what the best will look like. Wilson’s point is well taken and as long been adopted elsewhere. For example, an early edition of The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Rocks and Minerals (Chesterman, 1978) stated that minerals should be illustrated that “…are of finer quality than the amateur is likely to find; this is necessary to show clearly the distinctive qualities of color, crystal form, and habit” (p. 40).

Connoisseur specimens transcend aesthetics and the investment potential of minerals as commodities. The trend in some circles therefore to characterize connoisseurs as ‘aesthetically’ rather than ‘scientifically’ minded collectors altogether misses the point. Connoisseur thumbnail collectors, at the very least, tend to appreciate and recognize both perspectives as two sides of the same proverbial coin (Wilson & Houran, 2012). There is a clear understanding that specimens with both significance and aesthetics are rare scientific objects that represent the coming together of ideal physical conditions. Connoisseur specimens are beautiful and easily studied geological marvels that represent the highest level of development of a species. Collectors appreciate that the aesthetics exist precisely because of the scientific forces that were at play in the first place.

Availability of Connoisseur Thumbnail Specimens

Improved mining operations and a deliberate focus on careful specimen retrieval and preparation have produced an influx of interest and availability of connoisseur minerals of all sizes. Complementing new sources of specimens are frequent offerings from old collections. This has been especially good for thumbnail collectors. In fact, the past decade or so has seen a rise in the number of connoisseur thumbnails come to market from de-accessioned private collections. One could even argue that there has been an unprecedented flood of fine material from notable private collectors over this time span. Sometimes institutions also deaccession specimens, such as was the case with the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences (Wilson, 2006). Some of these collections were exclusively thumbnails but most were not – a fact that underscores how general collectors include smaller specimens when they are the best available of a species.

Sales of legacy collections like the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences, Herb Obodda (White, 2008) and James and Dawn Minette (Staebler, 2010) collections are always exciting events for collectors. There is also a considerable element of psychology at work that lends credibility and desirability to specimens from such famous collections. This is discussed in more detail below, but the notion of “social proof” is relevant here. Social proof is about conformity, and when many seasoned buyers flock around a recently released collection, less informed buyers will assume that they should participate as well. The tactic has notable benefits. For example, serious-minded newcomers to the hobby can efficiently enhance their collections by culling specimens from previous collections that were built on connoisseurship. The difficult work has been done in this scenario, i.e., selecting the best available specimens of given species. This can come at high financial costs; however, since connoisseur specimens are rarely low-priced and overlooked ‘sleepers.’ That said, significant collections, such as that of Salim Edde founder of the MIM Museum in Beirut (Wilson, 2014, 2015) or the Perkins Sams collection now with the Houston Museum of Science, have been built in good part by capitalizing on the previous connoisseurship efforts of others (and by the way, they will include thumbnails as well in their collections if they believe they are best of species or intellectually interesting, despite their reputations for having minerals of larger sizes).

Perhaps more than ever collectors have the largest and most diverse selection of connoisseur-level material. Still, the concomitant increase in prices has meant that it often takes significant financial resources to obtain the best pieces. The demand in the current market for connoisseur specimens, even thumbnail sized, suggests that the connoisseur community has healthy numbers and competition for the finest specimens will remain fierce. Many contemporary collectors, to be sure, have gained great reputations in the hobby by-passing larger-scale specimens in favor of connoisseur thumbnails.

This latter fact often puzzles those in the hobby who proclaim, “I collect minerals, not sizes” – a phrase attributed to collector Neal Yedlin (Wilson, 1990). True enough, to our knowledge American collectors are the only ones who consistently make size a rigid collecting requirement. The obvious and practical reason for focusing on size is overcoming restricted storage and display space. But the deeper and simpler truth is that thumbnail aficionados are under a friendly spell. Thumbnails are visually rewarding in large part because smallness defines their charm. In turn, this charm eclipses the mental demand for specimen size. The attribute of charm carries a dimensional quality as substantial as length or height.

Collecting small specimens is not new – the novelty comes from the recent development of assembling an entire collection of strictly (and mostly uniformly) small specimens. There are many ways to structure mineral collections, and thumbnails should be as valid as the other forms of specialization discussed by Dunn and Francis (1990) – after all, no one ever seems to say, “I collect minerals, not… localities, crystal classes, mineral classes, etc. Rather than a focus on size per se, it has been suggested that thumbnails are ultimately about collecting uniformly charming specimens that represent the highest level of development; these just naturally tend to be thumbnail size (Houran, 2014). Indeed, a well-chosen assembly of 1-inch specimens, mounted and lighted, is stunning. The visual appeal alone should guarantee that thumbnails will remain a center event in the hobby for many years to come.

Prevalence of Thumbnail Resources and Exhibits

Mineral shows understandably promote larger, spectacular specimens for public exhibits like the famous ‘Aztec Sun’ legrandite or the ‘Rose of Itatiaia’ elbaite. These are extreme mineral collecting, the stratosphere of mineral experience. This attention to ‘big and beautiful’ pieces at mineral shows; however, is typically balanced with smaller specimens like thumbnail displays of an educational or competitive sort. This exposes more people to the thumbnail niche, as well as helps to educate viewers on the current benchmarks as to what constitutes aesthetics and significance for given species or varieties, as well as for examples from specific localities.

Many recent exhibits and competitive cases have consequently built on the first two market forces (rise of connoisseur collecting and availability of thumbnails) such that the quality of the thumbnails shown typically serves as an extremely strong complement to – if not matches or exceeds in quality and diversity – the larger specimens on exhibit.

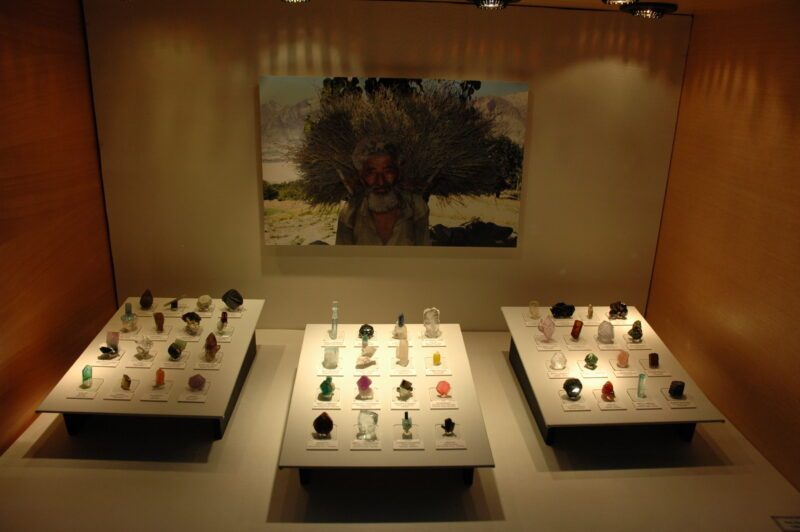

The single most active exhibitor popularizing this model in recent times, has to be Herb and Monika Obodda. A dealer since his childhood days, Herb traveled to Kabul in the late 1960’s and literally opened up the country for mineral collectors. Over the decades between then and the sale of his collection (to Rob Lavinsky at Arkenstone) in 2008, Herb collected for himself, and particularly kept many fine thumbnails and miniatures. As he says in an interview “Well, almost nobody would pay for good small things at the time I started this, so why sell them? I like rocks , too. I figured I’d keep some things”….and this led to what was surely the finest overall locality-constrained collection of Afghani and Pakistani thumbnails. After he (semi-)retired, he began exhibiting his personal collection at Munich, Springfield, and in a special exhibition in Tucson in 2007. Now dispersed into major collections all over the world, you can see in the photos below how the Obodda’s experimented with different display formats to show their thumbnails in the presence of, and synergistic with, larger specimens as part of a larger exhibition of the collection.

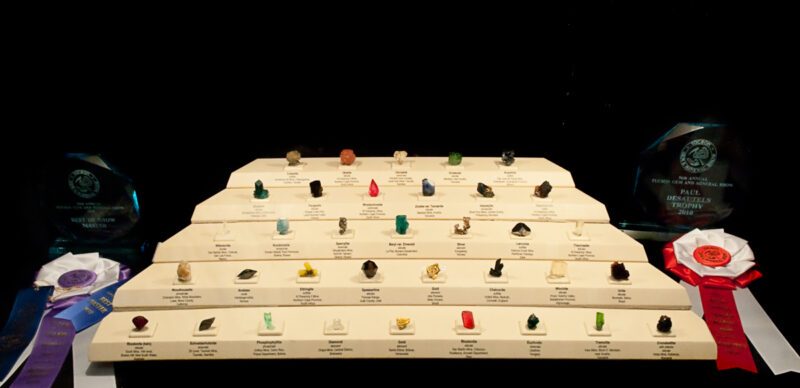

Some of the most prominent displays of connoisseur thumbnails in recent years include the following:

Denver Gem and Mineral Show

In addition to the formal competitions, major collectors routinely contribute top-quality thumbnail exhibits for educational purposes and general enjoyment. Typically these arrays do not focus on a given species but rather showcase a wonderful diversity of material and even collectors. These displays also serve as instructive glimpses into the personalities, styles and knowledge levels of the individual contributors, which can be educational and insightful for any collector. For example, the 2016 Denver Show featured a major thumbnail display by Ralph Clark that was specifically noted in the Mineralogical Record’s show report with a photo that took up nearly half a page (Moore, 2017, p. 138). In describing the impact of Clark’s case, Tom Moore wrote, “This was…a downright intoxicating array of best-of-all-possible thumbnails and “toenails,” and great was the wonder…of serious collectors (not only thumbnailers), who crowded this case all through the show” (p. 138).

Tucson Gem and Mineral Show (TGMS – Main Show)

This legendary event has traditionally set the standard for both competitive and educational displays. Many thumbnail displays have won competitions over the years, but most recently there has been a dedicated focus on making thumbnails featured educational exhibits. This trend began in 2008 with the American Mineral Treasures (AMT) project. The Crater of Diamonds, Pike Co., Arkansas locality (Howard & Houran, 2008) was represented by 16 famous diamonds finds, including the extraordinary 17-carat canary-yellow crystal from the Roebling Collection at the Smithsonian Institution (cf. Wilson, 2008). This case had the distinction of being the only thumbnail display among the AMT exhibits. Two years later, the authors coordinated a community exhibit titled “Connoisseur Thumbnails” – an unprecedented effort that was highlighted in the MR show report (Moore, 2010). The display brought together 92 specimens from 19 collectors. This successful format was repeated again in 2013 as illustrated in Wilson and Houran’s (2012) article, “The Elegant World of Thumbnail Minerals” (Moore, 2013b). It is also worth noting that in this same year mineral dealer and collector Diana Weinrich showed exceptional pieces from her private thumbnail collection.

Mineralientage München

Although many dealers at all price points have offered thumbnails throughout the 50-year history of this important show, the 2012 event was landmark. The show theme was “African Secrets” and for the first time in its history an exhibit composed exclusively of thumbnails was invited and featured. Titled “African Thumbnail Treasures,” this display brought together 182 specimens from 18 collectors representing four continents. An entire wall of the “African Secrets” exhibit area was cordoned off for four differently themed cases: Tsumeb, Classsics, Esoteric (rare or unusual species) and Gemstones (see Moore, 2013a). A fifth ‘potpourri’ case of miscellaneous African thumbnails was even added during final set up due to popular demand of the show organizers, who were pleasantly surprised that this array more than held its own compared to the myriad of larger and highly important African specimens displayed in the same area.

University of Arizona (UA)

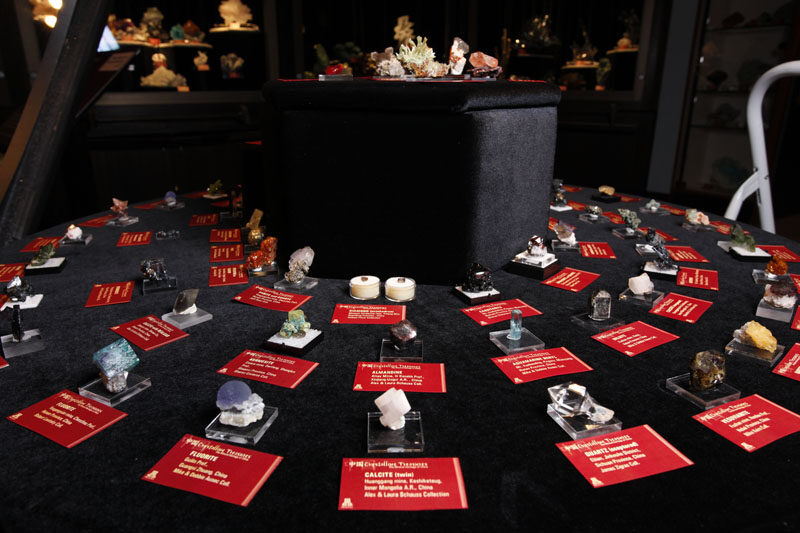

In 2013, the Flandreau Science Center and Museum at UA (Tucson, Arizona) launched a year-long exhibit called “Crystalline Treasures: The Mineral Heritage of China.” The exhibit predominantly featured the important Chinese collection of Dr. Robert Lavinsky (Moore, 2013b; Liu et al., 2013). To complement the wide assortment of miniature and cabinet sized specimens, Dr. Lavinsky and the other exhibit organizers invited a special case devoted to top Chinese thumbnails and toenail size specimens (65 in total, representing 16 collectors). This mini-display within the larger exhibit was presented via a round pedestal case in the middle of the exhibit hall allowing a full 360-degree view of all pieces. It proved to be one of the most popular aspects of the exhibit.

Commercial Media

There have been two especially noteworthy efforts highlighting connoisseur thumbnails. First, the Lithographie publishing firm released its highly anticipated book, The Jim & Dawn Minette Collection (Staebler, 2010). Secondly, Bryan Swoboda of Blue Cap Productions launched the new DVD series “Mineral Perspectives” in 2010, with an inaugural three-volume set devoted to connoisseur thumbnails (to date only the first two volumes have been released). This series utilized new photographic techniques developed by Swoboda and Jeff Scovil to present specimens in extremely high resolution, and almost 3D-like quality, while in 360-degree rotation. This approach allows viewers to study the specimens in supreme detail and under ideal lighting conditions.

Although we have not heard this discussed before, another consideration is that thumbnail displays like those mentioned above lend themselves well to psychological principles that help to entice viewers. To illustrate, photographs accompanying this article show various exhibits in recent years that have attempted to leverage such principles. It is interesting to explore their particulars.

First, most of the thumbnail exhibits have been community (or multi-contributor) exhibits that showcase famous specimens from respected contributors. Some collectors emphatically state that specimen provenance carries no weight with them, but many more collectors openly or privately acknowledge that it matters. Wendell Wilson and Wayne Thompson, for example, explain the attraction to provenance as a reflection of historical stewardship (Thompson, 2007; Praszier, 2012). More to the point, there is scientific evidence that contextual information like this biases our evaluations. Indeed, the perception of aesthetic objects is not rational but instead often is linked to accompanying information. For instance, Huang et al. (2011) compared how people’s brains reacted to paintings assumed to be authentic with their responses to paintings represented as fakes. They found that the responses to viewing an ‘authentic’ artwork were deeply pleasurable, likened to tasting good food or winning a bet. Yet, this aesthetic pleasure was replaced with brain activity associated with strategy and planning when people were told the artwork was ‘fake.’ Beauty is apparently not just in the eye of the holder; it is in part based on suggestion and expectation effects. Consider the Hope Diamond (Smithsonian Institution) or Mona Lisa (the Louvre). There are many other larger attractions in these museums, but these two famous artifacts are among the most popular and sought out of all the holdings. Clearly, the cognitive-emotional process that produces the experience of aesthetics and interest is not determined solely by the size of a target or focal point. The point is simply that larger specimens do not automatically command more attention. Mystique of an object is perhaps the most influential factor.

Second, there is the concept of visual balance and flow. Robinson (1999) presented an excellent overview of exhibit layout and design fundamentals, and additional guidance on effective displays was given more recently by Starkey (2012). Due to the smaller specimen size, viewers must take time to study thumbnail exhibits more so than cases containing larger specimens that can be easily and quickly ‘sized up’ from a distance. All things equal, mineral exhibitors arguably have a better opportunity to leverage the psychological principles of balance and flow in thumbnail arrays. More specimens on display provide viewers a greater diversity of colors, textures and shapes than in competing exhibits. This diversity alone often promotes sustained interest.

But we suspect that additional psychological factors explain why thumbnail exhibits engross onlookers so effectively. Vogt and Magnussen (2007) found that artists and laypeople visually evaluate pictures differently. Whereas trained artists are able to evaluate entire details of a broad scene, untrained laypeople tend to focus only on a select number of elements that are immediately most salient to the perceptual system. There is much to take in with a thumbnail exhibit, and in the absence of clear focal points, for example viewers’ eyes being drawn automatically to larger, dramatic looking specimens, people must take time to absorb all the content. This process of visual absorption is expected to inherently sustain interest because of a mixture of predictable and unpredictable elements. Think about it, viewers are experiencing a set of similarly-sized objects which is very predictable and, in the minds of many people, psychologically satisfying (harmonious or symmetrical) and visually cute. But the variety and diversity of species, colors, shapes, luster, etc in a well-designed exhibit simultaneously introduce an element of unpredictability.

Our sense is that the cognitive processing of this mixture of predictable and unpredictable elements creates an aesthetic experience akin to “pink noise” (cf. Voss & Clark, 1978). By way of explanation, there are three main categories of sound based on their mathematical elements: white noise, brown noise, and pink noise. White noise is random noise. A graph of white noise shows no specific organization, and the sound of white noise is often perceived as irritating and disturbing. Brown noise is very structured and organized. People usually perceive brown noise as mechanical and rigid. Pink noise is more structured than white noise but not as rigid as brown noise. This noise is called ‘1/f,’ meaning that it falls between the two extremes.

Pink noise is the mathematical nature of nearly all human-composed music, and this 1/f structure has been found in the mathematical elements of many social (behavioral) and physical phenomena as well (see e.g., Guastello et al., 2011). In short, well-composed thumbnail (and up to small miniature) exhibits may well elicit a viewer experience that is fundamentally the visual and cognitive equivalent of listening to an appealing musical score (cf. Houran & Bleess, 2014).

Discussion

Thumbnails are charming little wonders that have been prominently on the mineral scene for about 60 years now. It may be tempting to regard them merely as American curiosities, but fine specimens are regularly found within the world’s top collections. European collectors also certainly recognize great thumbnails when they see them. Knowledgeable senior collectors gave one of us (JB) a valuable hint early on – when looking through museum drawers, look for thumbnails. European collections have always held small specimens of superior quality. There may not be many, but they are there. Long before the term ‘thumbnail’ came into use, the great collections across Europe and elsewhere held small specimens whose charm alone, regardless of size, caused them to be curated, if not displayed.

The market forces discussed here have elevated thumbnails across the worldwide collecting community. With this in mind, thumbnail cases that win competitions remain controversial. Many contend that smaller and larger sized specimens should be relegated to different competition classes, since it is considerably more difficult to find larger specimens with the same level of perfection and aesthetics as many thumbnails. Thompson (2007) similarly noted that “Most mineral pockets will produce numerous smaller pieces for every larger piece. This rule applies to the ratio of good thumbnails to miniatures; miniatures to cabinets; and cabinets to museum-size specimens” (p. 22). There is no disputing this sentiment, but it would be misguided to assume therefore that connoisseur thumbnails are abundant in nature or on the market.

Case in point – not many years ago to show thumbnails in formal competition a display was required to hold fifty specimens and mostly of different species. Duplication was allowed so long as the specimens were of different locality or crystal habit. For the most part a collector kept to fifty different species, and this number certainly forced matters toward rarity, more so than the current thirty-two pieces now required. Frankly fifty was a high number, and very few exhibitors could hold quality throughout the display. A collection had a few ‘good ones’ but quality drifted downward fairly abruptly after about twenty-five specimens. This is still often true, but with the required thirty-two pieces in today’s competition a display has less far to drift. Quality points at the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show (TGMS) competitions are simply not easy to accumulate.

About twenty years ago the required 90-points to earn a blue ribbon in Masters Competition was lowered to 85. To state it bluntly, no one could keep the quality curve sufficiently flat throughout the range of thirty-two specimens; forget fifty, thirty-two specimens was a rigid test few exhibitors could pass. Speaking even more bluntly, not many can earn 85-points either. A person competing for a ribbon at the TGMS cannot risk losing any rarity points (5) or showmanship points (10) if planning to win a blue ribbon in Masters Competition at the TGMS, which is a major accomplishment. Connoisseur-level material in larger sizes is indeed comparatively rarer than thumbnails, but building a connoisseur thumbnail collection remains a considerable challenge. On the other hand, the challenge of the hunt is a large part of the appeal and satisfaction (Wilson & Houran, 2012).

The term thumbnail may not be eloquent, but it does serve to identify exactly what we are talking about. Crystalline excellence and specimen cuteness are the driving forces for connoisseur thumbnail collectors. For sure, specimens typically have razor keenness, and, in gemstones, near optical transparency. These added qualities characterize the extreme fineness that is widely appealing for those in the hobby. Regardless of whether one delves in this specialty, many collectors find viewing these little wonders as richly satisfying as viewing any other specimen sizes. This is especially so given that thumbnails often have attributes unavailable in larger pieces.

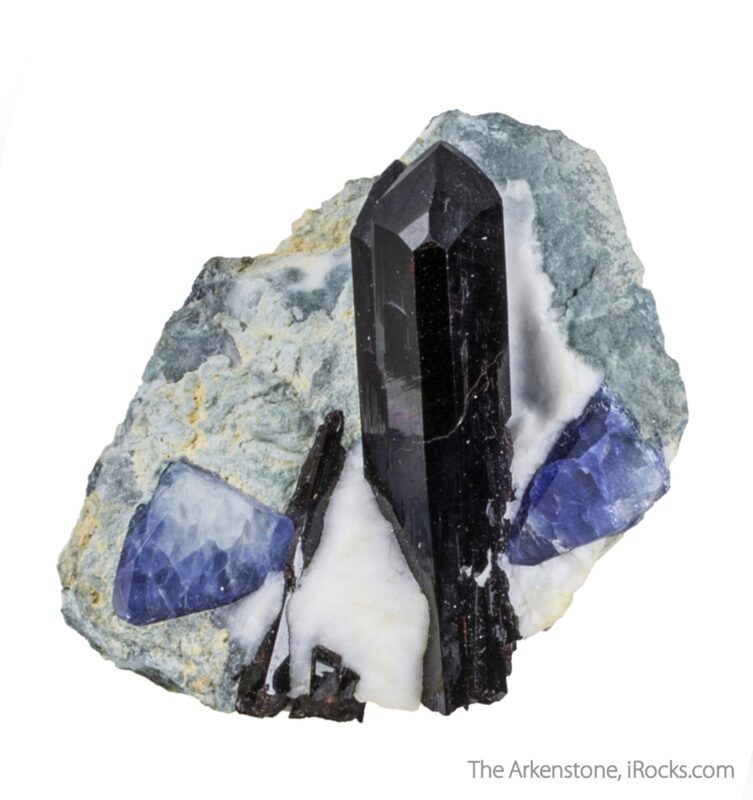

For example, consider sérandite from Canada. These crystals are fairly common in poorer qualities, but patient collectors can eventually find more desirable examples with well-formed crystals, good luster and a saturated color. Yet more can be expected from Mother Nature to yield a really superb example of the species defined by a 2.5-cm size – an association that rivals the dramatic color contrast of popular combinations like black neptunite on white natrolite or bluish-green microline (amazonite) and smoky quartz. Imagine translucent, sculptural peach sérandite crystals juxtaposed with large black spears of aegerine! Such a specimen goes beyond the moniker of ‘thumbnail’ to become extreme nature you can hold in your hand. Here are aesthetics and significance that, generally speaking, do not exist in larger specimens.

Many species and associations likewise offer equally artistic form in small size, and the many other pragmatic advantages to thumbnails are truly compelling. Some might even argue that thumbnail collecting has more to offer than any other niche in the hobby. Great things do come in small packages – and for that reason connoisseur thumbnails have had and will undoubtedly continue to enjoy an important and endearing place in the collector market.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article appeared in Lapis (Houran & Bleess, 2014), and we thank Dr. Stefan Weiß Tobias Weise and the entire Lapis editorial board for their permission to reproduce material. Appreciation also goes to Wendell Wilson, the Mineralogical Record and the many collectors who kindly contributed photographs or allowed specimens to be photographed by Joe Budd.

References

Bancroft, P. (1984). Gem & Crystal Treasures. Western Enterprises: Riverside, CA.

Chesterman, C. W. (1978). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Rocks and Minerals. Alfred A. Knopf: New York.

Cooper, M. P. (2010). Introduction. In The Lindsay Greenback Collection: Classic Minerals of Northern England (pp. 5-6). Supplement to the Mineralogical Record. Tucson, AZ: Mineralogical Record.

Currier, R. (2008). About mineral collecting: Part 1 of 5. Mineralogical Record, 39, 305-313.

Currier, R. (2009a). About mineral collecting: Part 3 of 5. Mineralogical Record, 40, 49-59.

Currier, R. (2009b). About mineral collecting: Part 5 of 5. Mineralogical Record, 40, 193-202.

Dunn, P. J., & Francis, C. A. (1990). Specialization in mineral collecting. Mineralogical Record, 21, 511-513.

Guestello, S. J., Peressini, A. F., & Bond, R. W. (2011). Orbital decomposition for ill-behaved event sequences: Transients and superordinate structures. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 15, 465-476.

Halpern, J. (2005). Criteria for selecting crystallized mineral specimens for a display collection. Mineralogical Record, 36, 195-198.

Houran, J. (2013). Connoisseur mineral collecting. Invited presentation at the Seventh Hong Kong Mineral Fair, April 27-28. The Mineralogy Society of Hong Kong: Hong Kong University.

Houran, J. (2014). Thumbnail specimens: Little treasures – collecting and competing. Presentation at the 4th Annual Dallas Mineral Collecting Symposium, August 22-23. Cox School of Business: Southern Methodist University.

Houran, J., & Bleess, J. (2014). Thumbnail Collecting – eine Philosophie des Sammelns. Lapis, 39, 12-28.

Huang, M., Bridge, H., Kemp, M. J., & Parker, A. J. (2011). Human cortical activity evoked by the assignment of authenticity when viewing works of art. Frontiers of Human Neuroscience, 5, article 134, 1-9.

Lininger, J. L. (1993). Portrait gallery: Charles H. Pennypacker (1845-1911). Matrix, 3 (1), 9-11.

Liu, G., Lavinsky, R. M., Meieran, E. S., Schmitt, H. H., Moore, T. P., & Wilson, W. E. (2013). Crystalline Treasures: The mineral heritage of China. Supplement to the Mineralogical Record. Tucson, AZ: Mineralogical Record.

Moore, T. P. (2002). Collector profile: Ralph Clark. Mineralogical Record, 33, 181-186.

Moore, T. P. (2010). What’s new: Tucson Show 2010. Mineralogical Record, 41, 275-294.

Moore, T. P. (2013a). What’s new: Munich Show 2012. Mineralogical Record, 44, 91-101.

Moore, T. P. (2013b). What’s new: Tucson Show 2013. Mineralogical Record, 44, 329-350.

Moore, T. P. (2016). What’s new: Denver Show 2016. Mineralogical Record, 48, 125-138.

Moore, T. P., & Lavinsky, R. (2013). In western eyes: How western museums and collectors judge mineral specimens. In Crystalline Treasures: The Mineral Heritage of China (pp. 25-28). Supplement to the Mineralogical Record. Tucson, AZ: Mineralogical Record.

Pardieu, V., Dubinksky, E. V., Sangsawong, S., & Chauviré, B. (2012). News from research: Sapphire rush near Kataragama, Sri Lanka (February-March 2012). Bangkok, Thailand: Gemological Institute of America. 82 p.

Praszkier, T. (2012). Collector interview: Wendell Wilson (USA). Minerals: The Collector’s Newspaper, issue 4, 13-18.

Robinson, S. (1999). Some observations (and tips) on exhibiting. Rocks & Minerals, 74, 263-265.

Smale, S. (2006). The Smale Collection: Beauty in Natural Crystals. Lithographie, LLC: Denver.

Staebler, G. (Ed.) (2010). The Jim & Dawn Minette Collection. Lithographie: Denver, CO.

Starkey, R. (2012). The good, the bad and the ugly: Museum displays – why do we keep making the same mistakes? Poster (#PS4-P07) presented at the IMA 7th International Conference on Mineralogy and Museums, August 27–29. Dresden: Deutsches Hygiene Museum.

Thompson, W. (2007) Ikons: Classic and Contemporary Masterpieces. Supplement to the Mineralogical Record. Tucson, AZ: Mineralogical Record.

Vogt, S. & Magnussen, S. (2007). Expertise in pictorial perception: Eye-movement patterns and visual memory in artists and laymen. Perception, 36, 91-100.

Voss, R. F., & Clark, J. (1978). 1/f Noise in music: music from 1/f noise. Journal of the Acoustic Society. 63, 362-371.

White, J. S. (2008) Herbert P. Obodda: dealer, gentleman, and collector extraordinaire. Mineralogical Record, 39, 315-330.

Wilson, W. E. (1990). Connoisseurship in minerals: science, beauty and history. Mineralogical Record, 21, 7-12.

Wilson, W. E. (1994). The History of Mineral Collecting, 1530-1799. Published as Mineralogical Record, 25(6), 1-243.

Wilson, W. E. (2006). Editorial: The Philadelphia sale. Mineralogical Record, 37, 498-499.

Wilson, W. E. (2008). The American minerals treasure exhibition, Tucson Gem and Mineral Show 2008. Mineralogical Record, 39, 171-222.

Wilson, W.E. (2013). Editorial: the best. Mineralogical Record, 44, 476.

Wilson, W. E. (2014). The opening of the Mim Mineral Museum in Beirut, Lebanon. Mineralogical Record, 45, 61-83.

Wilson, W. E. (2015). More from the Mim Mineral Museum, Beirut, Lebanon. Mineralogical Record, 46, 755-763.

Wilson, W. E., Bartsch, J. A., & Mauthner, M. (2004). Masterpieces of the Mineral World. Harry N. Abrams: New York.

Wilson, W. E., & Houran, J. (2012). The elegant world of thumbnail minerals. Mineralogical Record, 43, 219-262.