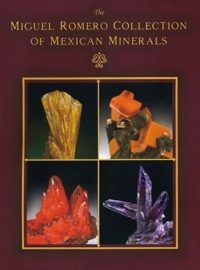

The Miguel Romero Collection of Mexican Minerals

18.7 cm, from the San Juan Poniente stope, Level 5, of the Ojuela mine, Mapimí, Durango, Mexico. “The Aztec Sun,” Jeff Scovil photo.

In 2008, Rob purchased the collection of Dr. Miguel Romero, who assembled a particularly significant and outstanding Mexican mineral collection. To memorialize the collection, we worked with the Mineralogical Record to publish supplementary volume highlighting Dr. Romero, his contributions to preserving the mineral heritage of Mexico, and his collection.

The book is available for free here, but the introduction, by Dr. Eugene Meieran, gives interesting insight into what happens when a collection is sold and thoughts about its dispersion.

If you’re interested in purchasing a copy, check to see if the Mineralogical Record still has them available for sale in their bookstore.

Introduction to The Miguel Romero Collection of Mexican Minerals

By Dr. Eugene Meieran

Originally published in 2008

I doubt that any serious collector of anything can pursue a collecting career without becoming aware of the amazing historical collections displayed in museums and other institutions. The mere names of these great collections conjure up strong emotions—of awe at the beauty and perfection of their specimens, and, yes, of an envious desire to own those specimens. As mineral collectors, we can all name the great institutions that have amassed fine mineral collections: the Sorbonne, Harvard, Yale, the Houston Museum, the British Museum, the American Museum, the Smithsonian, the Philadelphia Academy, the Los Angeles County Museum, etc. And we can often name individual collections within each of these institutions: the Roebling Collection, the Kunz Collection, the Vaux collection, and more. These historical collections were put together over time by dedicated private collectors, and eventually made their way into the museums of the world. We all have stood before such displays and thought, “Gee, I wish I owned that specimen!” Such envy is a characteristic (or a malady) of serious collectors!

One such impressive private accumulation was the Romero collection, which most recently resided in the Flandreau Science Center at the University of Arizona in Tucson. This particularly outstanding collection of Mexican minerals was put together over the years by Dr. Miguel Romero, and includes several of the most wonderful Mexican mineral specimens ever dug out of the ground, some of which indeed are widely recognized as the best mineral specimens from anywhere (so-called “mineral ikons,” using the term recently proposed by Wayne Thompson). In fact, the Romero collection of what might be called “Mexican Mineral Treasures” could be viewed as an analog of the spectacular “American Mineral Treasures” exhibits assembled for the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show in February 2008.

Miguel Romero in 1992, at his home in Tehuacan, showing the “Aztec Sun” legrandite, his most famous specimen, to Texas collector Imelda Klein in 1992.

As is the case with many fine private collections, the Romero collection was not seen by very many other mineral collectors for many years. It was originally kept in an office in Tehuacan, Puebla, Mexico, where it was seen only by the occasional serious collector who happened by—and by hoards of local school children who were regularly admitted for tours. I was fortunate to visit the Romero collection in the early 1980s, when I passed through the city during an unsuccessful trip to acquire some Las Vigas amethyst. So in 1997 I was thrilled to see the best of the collection come to Arizona and be put on display at the Flandreau museum! Along with the fine Arizona mineral collection and the displays of world-wide minerals in the museum, the Romero collection stood out as a peerless assemblage of great Mexican minerals. During the annual Tucson Gem and Mineral Show, thousands of visitors had the privilege and pleasure of seeing the best of the Romero collection on public display (thereby making it one of the most widely viewed mineral collections in the world).

Of course, while we as collectors privately covet museum specimens, we are always grateful that public museums acquire and display great pieces for us all to see. Museums preserve valuable natural and cultural artifacts and objects for posterity. So, as I said at the beginning, we mineral collectors look at public displays of private collections with mixed feelings: appreciation that great specimens are indeed preserved and displayed for public enjoyment, and jealousy that we do not own these wonderful objects ourselves!

The Romero mineral collection clearly represents the best that Mexico has to offer to the mineral connoisseur. It was put together by a person who knew, understood and loved mineral specimens and the mineral heritage of Mexico. And since Mexico is so well endowed with great minerals, the Romero collection stands out even among other great world-wide collections. And speaking personally, I really wanted some of those world-class specimens for myself, but I was equally appreciative of the fact that the collection was on public display for me and my fellow collectors to enjoy. Of course, I never thought that the best of the Romero collection would be sold to a private collector.

There are times when a great private collection or set of collections goes on display in a museum, and then later some or all of the specimens are sold or traded to the public, usually for one of three reasons. First, the museum may have so many equivalent specimens that it makes no sense to keep more of the same; the museum collection is enhanced by exchange of specimens with other institutions or collectors or dealers, and these transactions enrich both the private and public collections. Second, the museum may need funds for other exhibits or programs and, perhaps too often, minerals are the first to go because there is such a strong market for museum-quality specimens. And third, the collection may simply be on loan to the museum and is only on temporary display under its stewardship. It can be removed at any time at the discretion of the collection’s owner.

5-cm view, from the Nevada mine, Batopilas, Chihuahua, Mexico. Ex. Romero collection. Joe Budd photo.

This third scenario was the case with the Romero collection: the Romero family had retained ownership while the collection was on public display in Arizona, and they ultimately decided to put it up for sale. We are naturally saddened by the fact that the entire collection is no longer on exhibit. However, the situation is not as bad as it might seem. We can be heartened by the fact that suites of Mexican locality specimens will be retained permanently by the University of Arizona, through the efforts of Rob Lavinsky, the dealer who transacted the sale. The Arizona specimens have gone to the leading private collector of Arizona minerals, where they will surely be well cared for, and although some of the Mexican specimens have been dispersed, Rob has arranged for the core of the Mexican collection to remain intact with a private collector who is planning eventually to open a mineral museum overseas. So, although the unity of the Romero collection is lost, some of it will remain available for study by the public at the Flandreau Science Center in Arizona and the most of the major Mexican specimens may someday be on exhibit together once again in a public museum.

Since the vast majority of private collections are ultimately broken up and their cohesiveness totally lost, it is gratifying to me as a collector to see the best of the Romero collection documented in this book, and to know that most of the collection will be preserved in major segments. In addition, 1,200 specimens still in the Romero Mineralogical Museum in Tehuacan will remain there, and a systematic collection consisting of 5,500 specimens is being donated by the Romero family to the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. I look forward to seeing portions of the Romero collection once again, albeit in different museums. Given that the Romero family has found the sale necessary, this is indeed the best possible outcome.

Read the Mineralogical Record supplement featuring Dr. Miguel Romero’s collection online!

Read the Mineralogical Record supplement featuring Dr. Miguel Romero’s collection online!