Collector interview: Alex Schauss

Interview by Tomasz Praszkier. Republished with permission from Minerals: The Collector’s Newspaper, 2014, issue no.8.

This time in our Collector Interview series we have the pleasure of talking to Alexander Schauss, vice-president of Friends of Mineralogy, and one of the world’s leading collectors of competition-quality thumbnails. Alex shares with us some of his family history, and talks about his career researching nutrition and botanical medicine, and how these disciplines relate to his passion for mineralogy.

Tomasz Praszkier (Minerals): Alex, before we talk about minerals please tell us a little about the interesting history of your family and how you came to the USA?

Alex Schauss: I come from a long line of musicians, some quite famous, starting with my great-grandfather who was a German composer. My father was a concert pianist who taught piano at the Berlin Conservatory before World War II (WWII). My grandfather was the concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and Quartet from 1928 until he retired in 1962. Well known as one of the best violinists in the world, he began criticizing Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist Party in articles that appeared as early as 1933, and the family was frequently threatened by the SS for his outspoken comments.

Once he learned that the Nazis were rounding up Jews, he assisted numerous Jewish members of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra financially and with letters of recommendation, which helped them find positions in American orchestras. I was shown many of these letters and documents by the orchestra’s historian during a visit to Leipzig in 2011.

I was born in Hamburg, but 90% of the city was destroyed by the end of the war. Food was very scarce and there were no jobs for professionals such as my parents. Life was very difficult, especially for those who had opposed Hitler. Many Germans felt that those who had opposed the National Socialist Party had betrayed their country.

So we came to America as immigrants in 1953 with just $24.00, and we lived in a gang-infested slum in the upper west side of Manhattan while learning English and trying to find work.

TP: How did you start your adventure with minerals?

AS: We soon became friends with a family that had just arrived from Puerto Rico; their son, Sammy, was seven, the same age as me. The two of us roamed around Manhattan, trying to stay away from the gangs and the violence in our own neighborhood.

One day we were walking along the Avenue of the Americas in midtown Manhattan and we stopped to watch construction workers blow up the granitic gneiss bedrock with dynamite and haul the rock away. It was exciting stuff!

We asked the truck drivers where they were taking the rocks and they told us the location near the northern tip of Manhattan Island. We headed home and we each borrowed a hammer and a small shovel from a kind gentleman who owned the local hardware store, and then we took the subway north to see what we could find.

We brought many “treasures” back with us, and took them to the mineralogy and geology department of the American Museum of Natural History, just a few blocks from our respective apartments. This is where I met Dr. Frederick Pough, who was rather amused by the rocks we brought him, since they were nothing more than samples of muscovite, orthoclase, and quartz, all commonly found in Manhattan’s schists, pegmatites and gneisses.

One day I brought Dr. Pough a specimen with a vug which contained an exceptional dark crystal that turned out to be the largest columbite the museum had seen. He asked me if the museum could keep it, and I agreed that it could. When I returned a few weeks later with more rocks from another Manhattan site near the Williams Bridge, he showed me the Manhattan mineral display in the main hall, where he pointed out the specimen I had given the museum in the case. Talk about cool!

Since I had given the museum that mineral he offered to give me a specimen from its collection in return.

He took me to the rear section of the main hall where one could see stunning cabinet-sized specimens of fluorite and galena. He opened a drawer below a display case with a superb galena from Joplin, Missouri, and asked me to choose from one of the two “extra” galenas that were “taking up too much room”.

I picked one, which he agreed was the best, and carefully wrapped it up in a sack. “You picked the best of the two, Alex, you just might make a good mineralogist some day”. Talk about encouragement!

Needless to say, I returned repeatedly to help him in any way I could in the curator’s office until he allowed me to handle hundreds, and eventually thousands of specimens. This continued into my junior high school years. I was fortunate that my junior high school was located just across the street from the museum.

TP: Can you tell us about your attempt to “rediscover” the Levison chrysoberyl locality in Manhattan?

AS: During one of our visits to the American Museum of Natural History, Dr. Pough showed Sammy and me a map of where one of the finest (classic V-twinned) chrysoberyl crystals in America was found, in Manhattan Island, no less!

It was discovered on June 16, 1893, on the north side of 88th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, at the excavation site for a five-story tenement building that, purely by coincidence, was the apartment building we lived in (from 1955-1968) on the 4th floor. The specimen is known as the “Levison Chrysoberyl”. It was discovered by Wallace Goold Levison (1846-1924), one of the most prolific collectors of New York City minerals, and a member of the New York Mineralogical Club. He was also the first editor of the American Mineralogist (founded in 1916).

Well, foolishly, Sammy and I went home and broke through the concrete pad at the back side of the apartment building and began digging for chrysoberyl crystals. The building superintendent discovered what we were doing and chased us off, yelling and screaming. We told our parents what we had done. My dad went to see him with me in tow and had me apologize. He then paid the superintendent the money to replace the broken concrete. I also had to help him take the garbage cans out for a month and I was grounded from leaving the neighborhood. It took me over a year and a half to reimburse Dad for the cost of that concrete.

TP: Do you think that if you hadn’t been lucky to meet Dr. Pough your mineral passion would have evolved in the same way?

AS: It’s hard to know, but there is no question that he taught me so much, especially about crystallography and how to recognize a world-class specimen. I had no idea of the status of the collection at the American Museum until many years later, when people in the field of mineralogy helped me realize how fortunate I was to have been befriended and trusted by him to handle minerals and to be a junior volunteer. Of course, I was very fortunate in living so close to the museum.

TP: Did your parents support your hobby?

AS: My mother was particularly supportive of my mineral collection as it grew over the years because her father, who had two PhD’s in engineering (one from the Sorbonne University in Paris, the other from the University of Peters-burg in Russia), had collected gems and minerals from the Ural Mountains. He was very wealthy, since he owned a large engineering firm that took on major construction jobs in Russia and Eastern Europe.

My mother had been about to start medical school in Belgrade when the Nazis invaded Yugoslavia. They destroyed her medical school and took over the family’s mansion as some kind of headquarters just outside of Belgrade. Mom joined the underground and used her wealth, including her father’s collection of rubies, emeralds, alexandrites, etc., to smuggle Jews out of the country. I didn’t know about this until many years later when I visited Israel and learned of her bravery. When I came home and asked her why she had never told me about her heroism, she responded, “It was what anyone would have done”, and told me not to bring up the subject again.

TP: When did you start becoming seriously involved in the mineral collecting community; going field collecting and visiting mineral shows?

AS: Well, I can’t really think of a time in my life when I didn’t find myself digging holes and taking an interest in mineralogy. When I was in high school, my girlfriend lived in Little Falls, New York. We spent quite a bit of time digging for Herkimer “diamonds” not far from her family’s home.

One summer I attended Western New Mexico University in Silver City and dated the daughter of the superintendent of the Chino Mine which, at that time, was the largest open pit copper mine in the world. When I asked him if I could collect specimens in the mine, he found it hard to say “no” to his daughter’s boyfriend.

It is worth mentioning Dr. Pough’s influence when I first met Ed McDole. I arrived in New Mexico to attend university in 1966 and joined the Albuquerque Gem and Mineral Club. The Club’s president, Dean Wise, also known as “the dean of mineralogy”, encouraged me to visit the Tucson Gem and Mineral Society (TGMS) show in February 1967, which I did.

At the time the TGMS show was held in a large tent near the Tucson Airport. Miscalculating the starting date of the show, I arrived a few days early. A man in a white shirt, black pants and black shoes, and with the stub of a cigar in his mouth, came up to me and noticed that I looked lost. I told him I was looking for the TGMS show, whereupon he invited me to look at a few “rocks” in the trunk of his black Lincoln Continental. My eyebrows immediately went up, after which I told him what each specimen was, where it came from and, in some cases, the year it was probably found in. He took the cigar out of his mouth and asked me how old I was. “Eighteen, sir”. He replied: “How is it possible that you know so much about these minerals?”. I told him about my years at the American Museum and the knowledge I had gained from Dr. Pough.

He said: “That explains everything”. Clearly, he knew Dr Pough; then he introduced himself as Ed McDole. I was honored to meet him. Even though I had just a few dollars to buy specimens, he introduced me to people around the show floor, saying something about my being one of “Pough’s kids” from the American Museum; always with a cigar in the corner of his mouth.

Ed died in 1970 and, given this background, you can imagine how pleased I was to win the Ed McDole Trophy several years later at the 1989 TGMS show for the best mineral case (of thumbnails, no less).

TP: What was your first specimen and your first “serious” specimen?

AS: My first specimen was a piece of gneiss, 15cm by 8cm, from Manhattan Island (New York City). I still have it, but it’s not an attractive specimen!

The first serious specimens were all self-collected in New Mexico. They included a 90 cm by 60 cm block of botryoidal smithsonite collected in 1967 from the Kelly Mine. I sold it the same year for$100, and I gave $50 to the owner of the mine. The mineral dealer I sold it to in Albuquerque wanted me to break it in half so that it would fit in a “beer flat”. He travelled to many rock and mineral shows in the western United States in his van and had all of his specimens in beer flats.

Since the specimen was too large, he didn’t want to buy it unless I cut it or broke it in half. I was shocked that he would take this specimen which took me several hours to get out of the mine undamaged, and want to break it in half. I don’t know whether he broke it in half, but I certainly didn’t.

Selling the Kelly mine smithsonite was not an easy decision. Yet $100 was a lot of money for a student at the time. Also, there was no place to store it in the dormitory room shared with another student. In today’s market, that specimen would probably sell for over $250,000.

TP: Your plan was to study geology but finally you ended up as a nutrition/food scientist. How did this happen?

AS: I would have majored in geology had I not taken a trip to southern New Mexico, where I literally stumbled onto the location of a “lost” Indian tribe that dis-appeared around 1500 A.D., that archeologists had been searching for.

While traveling along a remote dirt road, I decided to stop and take a look at a map and figure out where I was. I spot-ted a butterfly in the middle of the desert and followed it for a few hundred yards. All of a sudden there was a spring and next to the water were shards of Indian pots that looked like some pottery a professor in the history department had shown us. I took a few pieces back to the university. A few days later the professor told me I might have found the lost tribe of Mimbres Indians everyone had been searching for. For this discovery, I was inducted as a sophomore into Phi Alpha Theta, the national honorary society in history, which motivated me to major in history, rather than geology.

My interest in the effect of nutrition on brain function and behavior, which became my career, began in 1970 when I worked for the Second Judicial District Court of New Mexico as a probation and parole officer, which also required my being a deputy sheriff. The case histories that influenced the realization of how important diet could be to human health and behavior are discussed in the first two books I authored in 1978 and 1980, Orthomolecular Treatment of Criminal Offenders, and Diet, Crime and Delinquency, respectively.

The first book had the signature of two-time Nobel laureate, Dr. Linus Pauling on the cover, which attracted a lot of attention. It was the first of 23 books that I’ve authored or coauthored on nutrition and botanical medicine.

When I moved to South Dakota in 1975, I saw dramatic effects of diet in rehabilitating adolescent criminal offenders. This confirmed my earliest suspicions that this was a fertile field for research.

TP: Your scientific work is somehow connected with minerals and chemistry. The title of one of your many books is “Minerals, Trace Elements and Human Health”. Can you tell us about your scientific work?

AS: Studying minerals both from a mineralogist’s perspective and in terms of my interest in the effects minerals can have on human health has exposed me to a wealth of scientific data. Occasionally, the information has direct applicability to problems experienced by miners exposed to toxic metals such as lead, cadmium, and arsenic.

A good example occurred in 2013. A group of miners had been working in an old base metal mine, collecting specimens of wulfenite, mimetite, barite, etc., leading to excessive absorption of heavy metals. After failing to respond to conventional methods to remove them, they were informed that a dietary supplement that had been submitted for a safety review by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) might help them. This natural product has been known for decades for its ability to remove heavy metals.

Heavy metals can cause inflammation and act as pro-oxidants damaging cells, including neurons in the brain and central nervous system, which is why they are referred to as neurotoxic. The miners were also advised of a fruit whose pulp has been demonstrated in experimental studies by the USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) to exhibit potent anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant bioactivity.

In just a few months the combination of these two natural compounds resulted in a dramatic reduction in the miners’ blood levels of heavy metals; soon afterwards they were back in the mine.

It is important to understand the relationships between metals to appreciate how they can work together or against each other. For example, selenium can protect against mercury exposure, zinc against cadmium, calcium against lead, etc. Such relationships and other information about nearly 30 minerals essential to human health are discussed in my book, “Minerals, Trace Elements and Human Health”.

TP: We talked a little about your time in New Mexico, but you’ve also lived in South Dakota and, more recently, in Washington state. What collecting opportunities have you had there?

AS: While in South Dakota I was fortunate to learn about some superb, gemmy, golden barites found in concretions in the Pierre Shale in Elk Creek, Mead County. I quickly learned how to extract the best barite specimens, and filled over a dozen flats with fine, gemmy examples during several visits. I took them to Tucson a few years later and traded them at the Old Desert Inn for some very fine thumbnail specimens from Tsumeb, Mont St. Hilaire, and Broken Hill.

In 1977, I moved to Washington State and bought a house near Tacoma. This was an ideal location to go up and down the Cascade Mountains looking for minerals. I met Bart Cannon from Seattle, who gave me permission to dig for garnets on Vesper Peak. Anything I found I could keep, and this provided me with valuable trading material at the Old Desert Inn in Tucson each year. The state geologist, Raymond Lasmanis, learned that I had a large group of kids from the Puyallup Gem and Mineral Club wanting to learn more about the geology of the state. He would call me whenever a forest road was being built in the Cascades and promising minerals had been located. On some of these trips the kids would find world-class zeolites, some of which I donated to overseas museums as my research on nutrition carried me to countries all over the world.

TP: So presumably your overseas travels also afforded you some interesting collecting and trading opportunities?

AS: In 1983, I was invited to lectures given on the campuses of universities around South Africa. This allowed me to visit the Kalahari Manganese Field, and to meet with mineral collectors around the country, including Desmond Sacco. He kindly invited me to dinner at his house, after which he showed me his remarkable mineral collection. While I was visiting a rock shop in Cape Town, a miner from the Kalahari manganese mines appeared with nearly 20 flats of some strange new minerals none of us had ever seen before. Later we learned that these were ettringites, charlesites and sturmanites. I was fortunate to have the pick of these, and they proved to be highly sought after specimens in Denver and Tucson that allowed me to trade for some rare Tsumeb specimens.

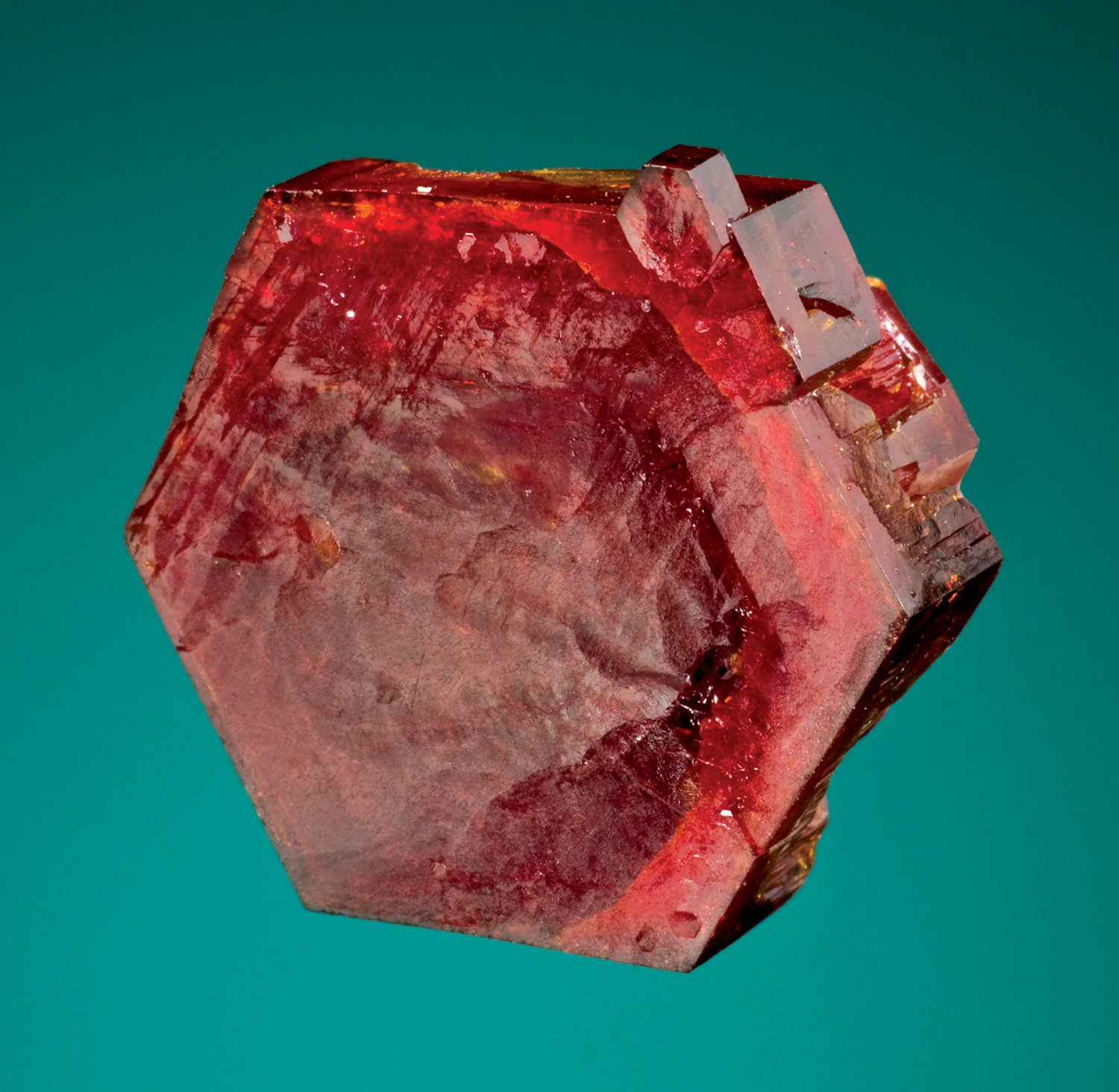

In 1980, I was invited to give a lecture at the University of New South Wales, in Sydney, Australia. The next day I went to visit the famous Australian mineral collector, Albert Chapman, at his house just outside of the city. Albert encouraged me to visit Broken Hill, one of the locations on my bucket list, which I did. This is where I found one of my favorite garnets, a superb, red, twinned spessartine crystal, just lying on the ground; it was included in the case that won the 1989 Ed McDole Trophy at the TGMS show.

TP: Over a number of years you have created one of the world’s best thumbnail collections. How and why did you start to collect thumbnails? How long did it take to build your collection?

AS: By 1968, I had traded most of the specimens Dr. Pough gave me, so that I could start building a serious thumbnail collection. My income as a college student, and then working for the government for ten years, only allowed me a budget sufficient to buy a few specimens a year at best, so I had to be very selective about what I purchased. The rest of the collection, built over many years, was acquired by trading specimens or by field collecting.

Exceptional specimens, even of very rare minerals, that are thumbnail-sized are relatively affordable compared to larger pieces. Many minerals rarely, if ever, get any larger than thumbnail-size, so those minerals became particular targets for acquisition. Thumbnails are also easy to store and they take up far less space than larger specimens.

During the formative years of my collection, finding exceptional specimens was not easy for two reasons. I didn’t have the money that many well-to-do collectors had and, often, there weren’t many exceptional specimens available to acquire. With perseverance and luck, being at the right place at the right time, and by attending scores of mineral shows over the years, a quality collection emerged. Entering a case of 35 minerals and/or 25 specialized thumbnail-sized minerals at regional and national American Federation of Mineralogical Societies (AFMS) competitions helped me learn from judges, collectors, and dealers, which minerals were outstanding, and why.

By 1980 I was a member of the San Diego Gem and Mineral Society, and I scored just a few points less than Jim and Dawn Minette’s thumbnail case at a California AFMS competition. The Minettes had a world-class collection of thumbnails, so I was very pleased with that result. Competing in AFMS-sponsored regional and national competitions allowed me to gauge my progress compared to other advanced collectors year-to-year.

TP: I’ve heard that your first thumbnail collection was stolen?

AS: In 1984, I won my first trophy for thumbnails at the TGMS show. However, I still needed just two more exceptional thumbnails of rare species from the Tsumeb mine to be able to enter a Tsumeb-only case into competition. To preview the Tsumeb-only concept, along with a case of some 60 other thumbnails from worldwide localities, I took the collection to the 1985 Pacific Northwest Friends of Mineralogy (FM) meeting in Washington State. It was held in what was then my hometown of Tacoma. Unfortunately, while registering for the meeting, two vans and my car where broken into and all of my minerals stolen, in less than ten minutes! The theft literally wiped out my collection, including 20 rare minerals from Tsumeb, acquired over many years.

The theft of the collection was more than personal; it was a loss to the mineralogical community since we, as individuals, are merely the custodians of the specimens. Having failed to protect the collection, I decided to quit collecting minerals altogether. The loss was very depressing. However, my wife persuaded me not to give up, and I will always be thankful to Laura for her persistent encouragement and support.

By 1988-1989, I was able to put together a strong enough collection to win nine regional and national AFMS trophies at the Masters level, the Richard M. Pearl Trophy for the best mineral species at the Denver Gem and Mineral Show in 1988 (a gold specimen from Venezuela), as well as the cherished Ed McDole Trophy at Tucson in 1989 for best mineral case.

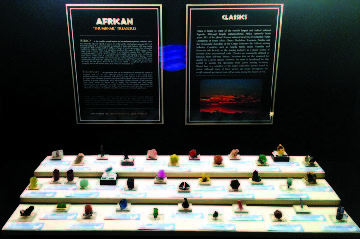

In 2012, Jim Houran, a consummate Texas-based thumbnail collector, and I traveled to Munich to display five cases with a total of 188 thumbnail specimens for the African Minerals special exhibit organized by The Munich Show. The collection included many of the world’s best African thumbnails loaned for the exhibit by collectors around the world. We were surprised and delighted by the response the exhibit received, evidenced by the thousands of people that spent time looking at those cases. It was the first time in the 49-year history of The Munich Show that a special exhibit of thumbnail-sized specimens had been displayed.

TP: Your collection has won many prizes. Which one is the most important for you?

AS: They all are. Each represents a mile-stone that contributed to the quality and range of specimens in the collection today. The awards also remind me of the pleasure derived from watching people see the specimens at various mineral shows, as well as the social interactions it affords to learn more about mineralogy and to make friends and see other collections.

The Ed McDole Trophy earned in Tucson is particularly meaningful since I had a chance to meet and get to know Ed before he passed away in 1970. Receiving the 2010 Paul Desautels Trophy for best mineral case in Tucson was another milestone since both the Ed McDole and Paul Desautels trophies were won with thumbnail specimens.

TP: Are you very strict about specimen size? Why collect according to size, rather than by locality, or by species? How many specimens do you have?

AS: Selecting thumbnails that meet regulation size has proven a way to acquire exceptional specimens on a limited budget.

It is well known that collecting thumbnails is a North American thing, as both the U.S.A. and Canada have encouraged competitive cases to be entered and exhibited at major mineral shows for many decades.

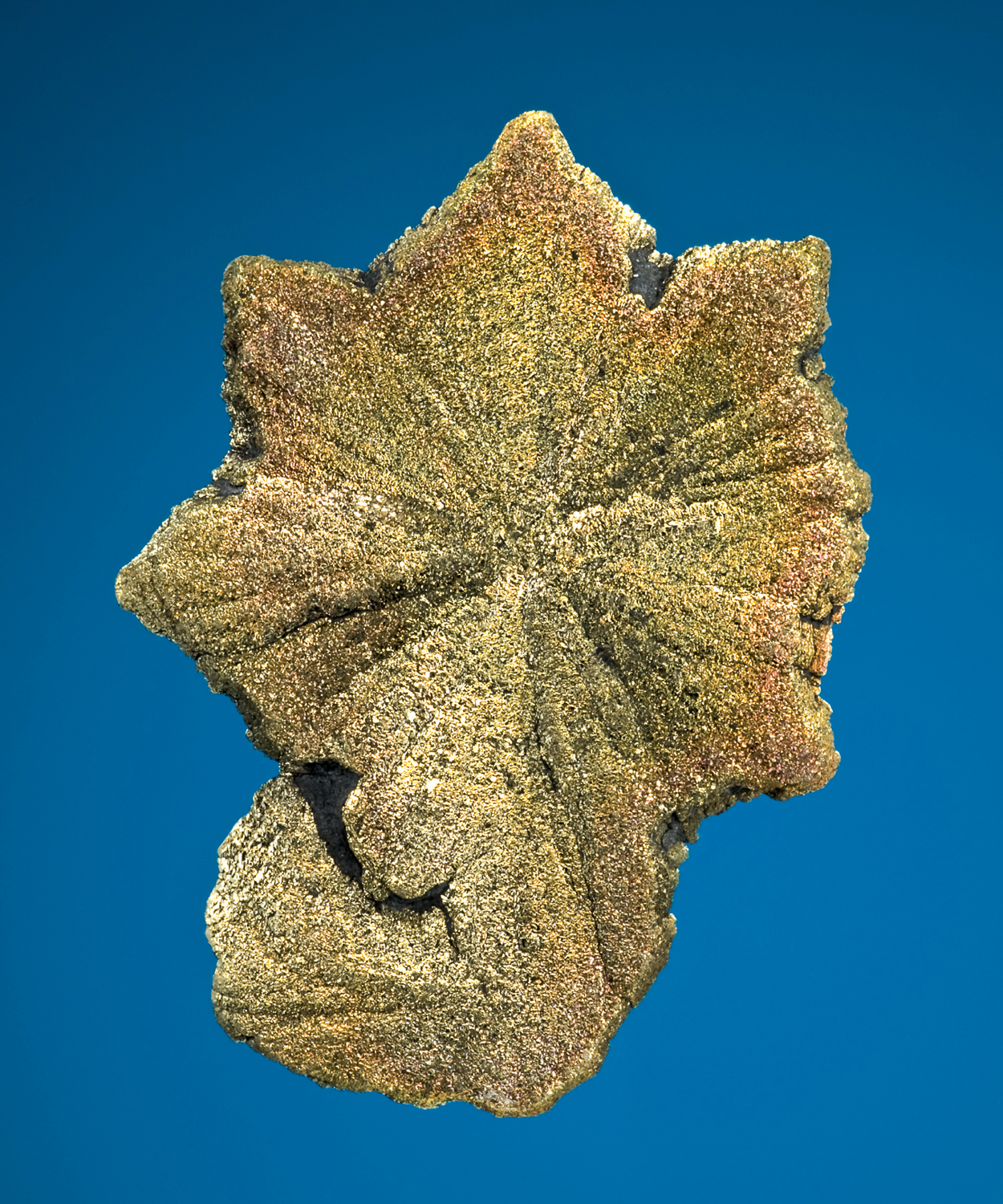

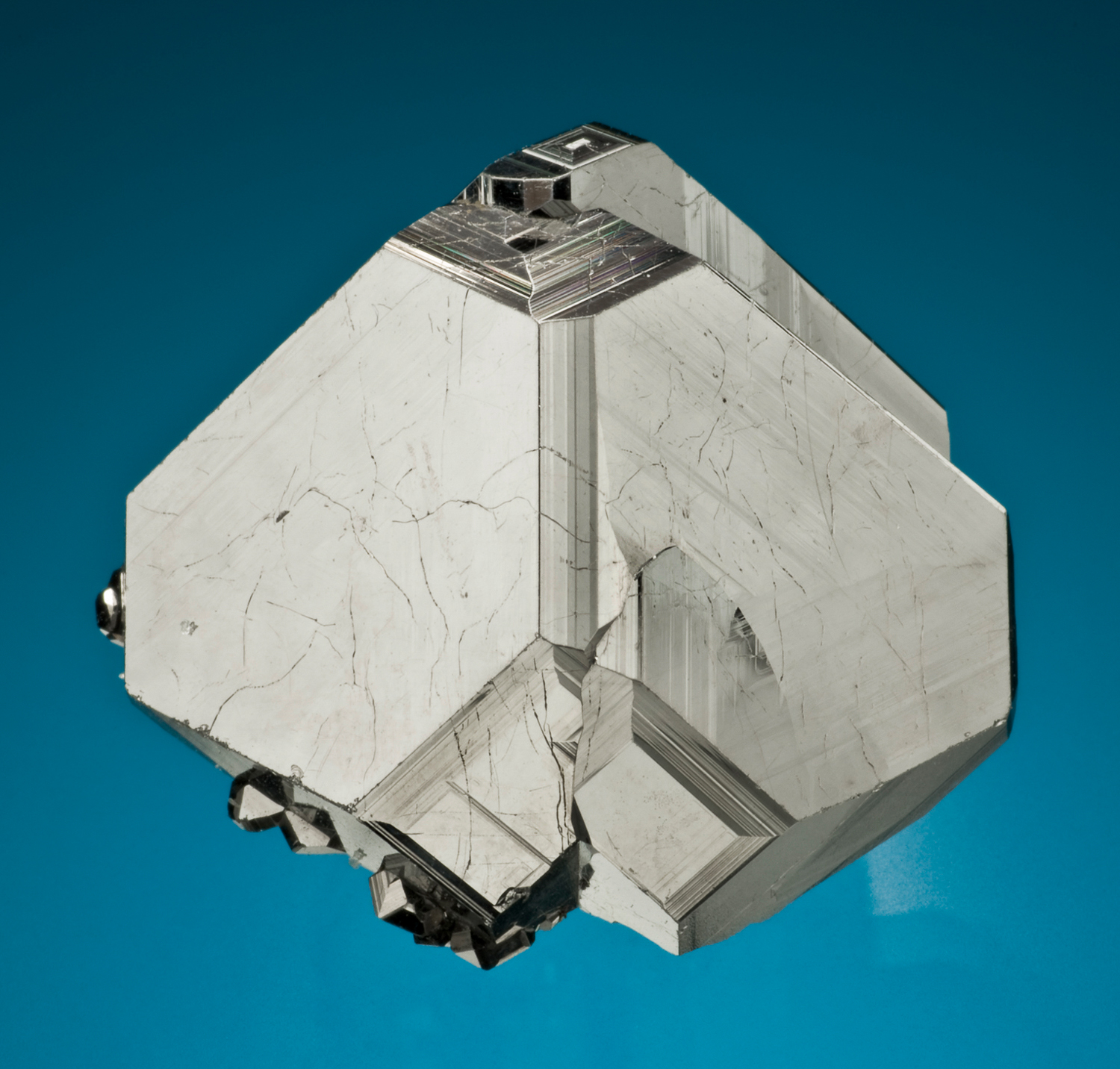

Since it is not possible to acquire or trade for an exceptional thumbnail each year, I made the decision years ago to maintain a sub-collection of the best thumbnail-sized calcites, hematites, and pyrites, with the balance of the collection covering all species and with a world-wide scope. Currently 17 specimens are on display at the University of Arizona’s mineral museum.

TP: Which specimen in your collection do you consider the best one and why? Which one is your favorite?

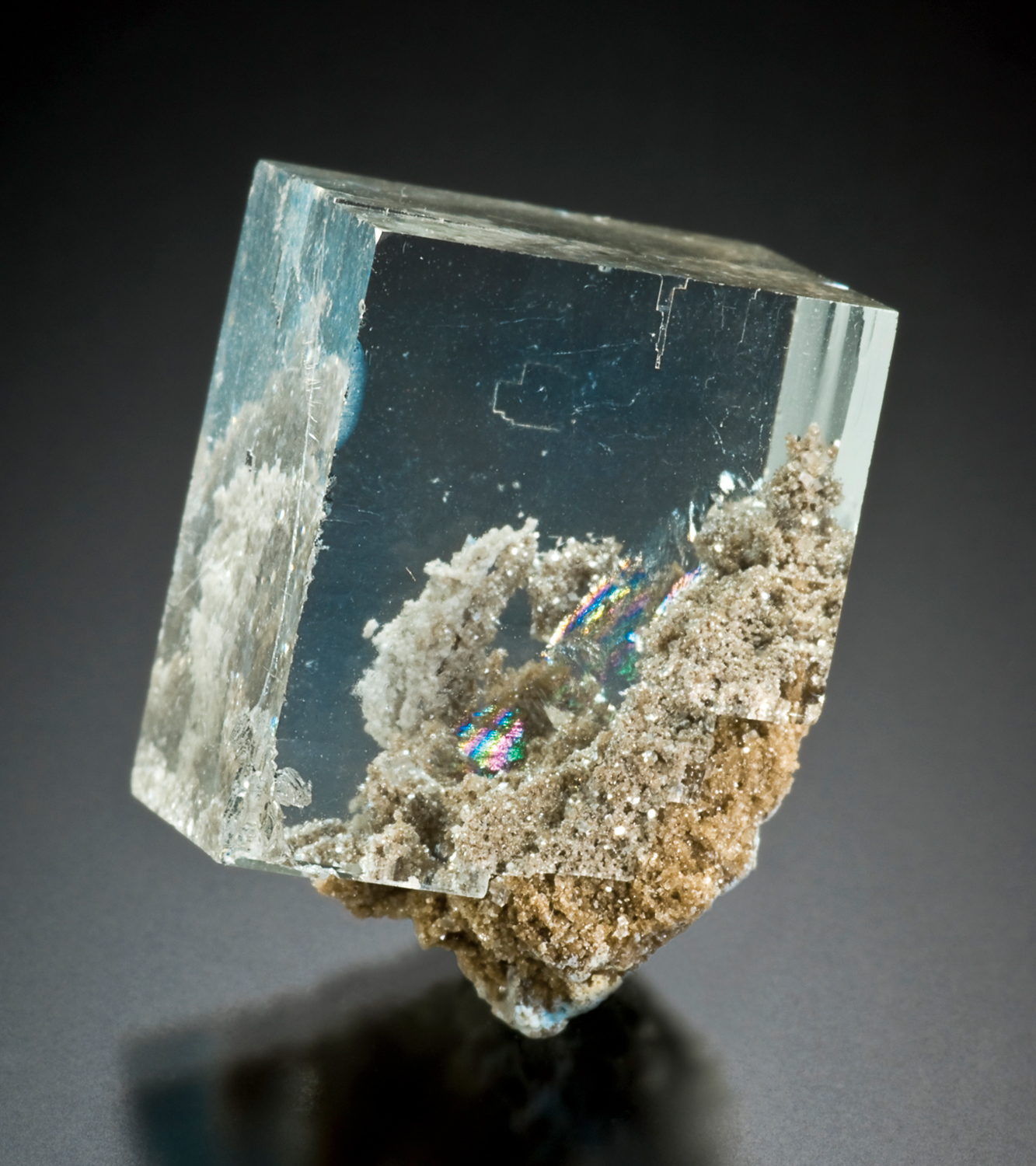

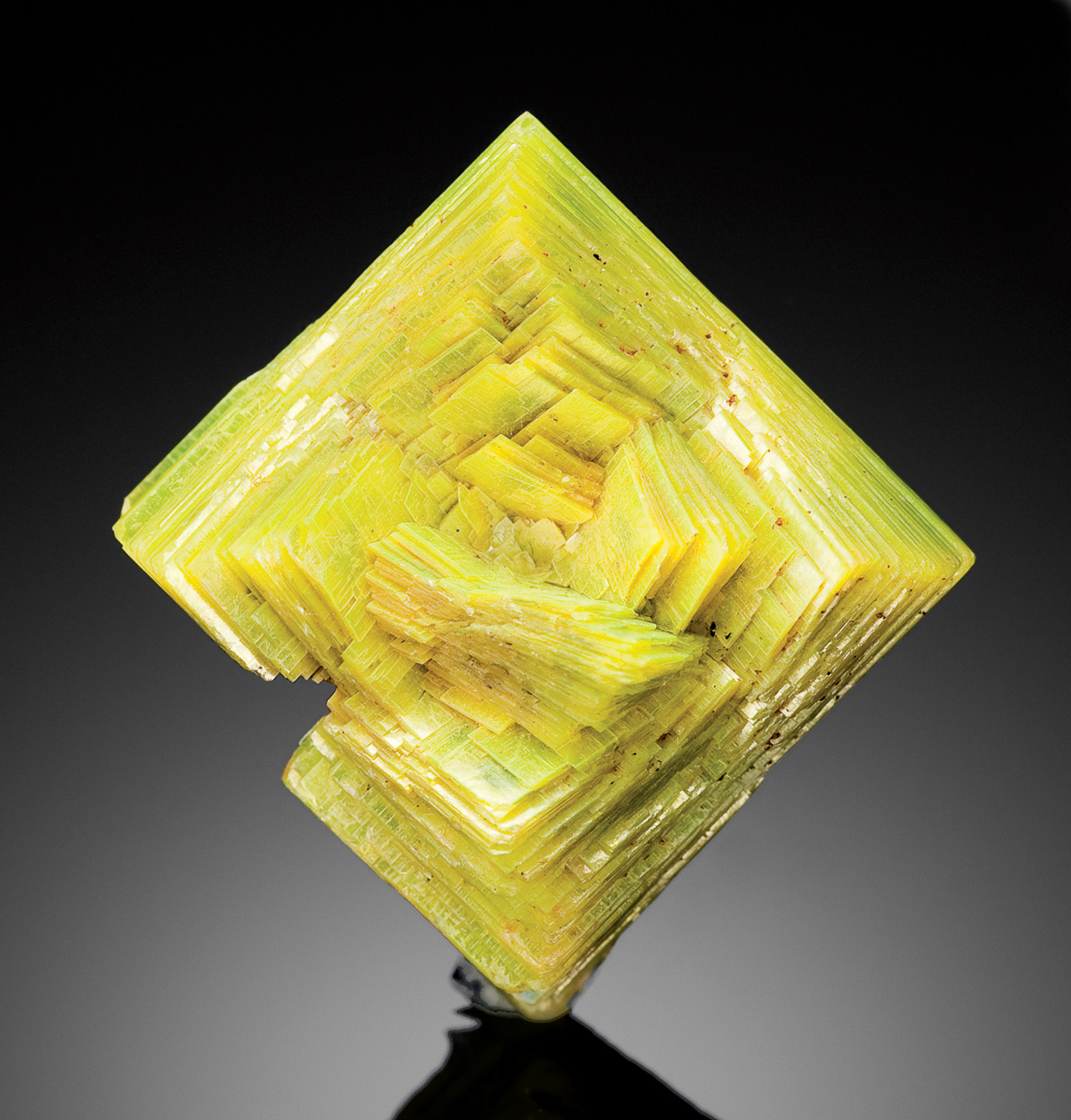

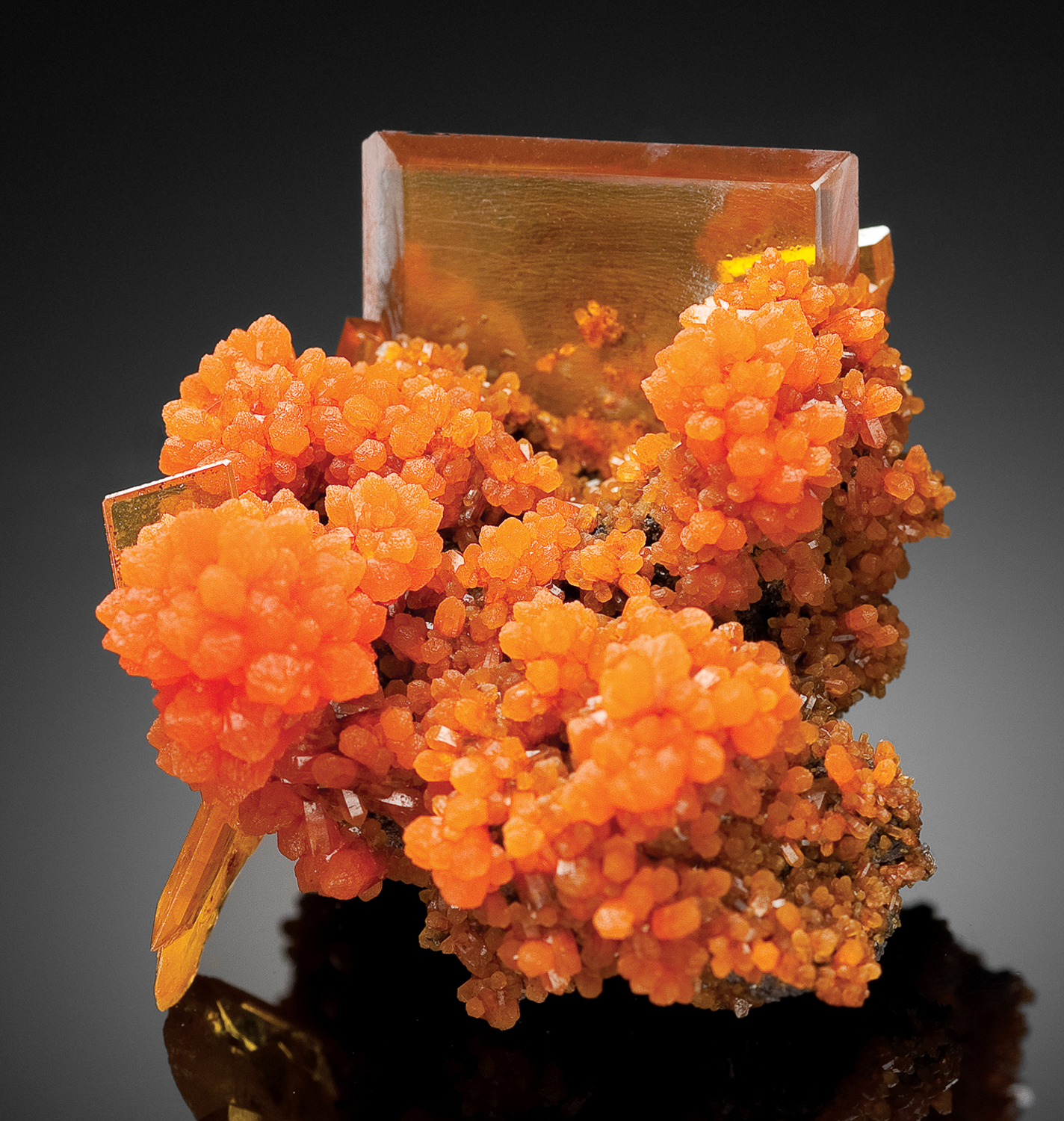

AS: That’s like asking a parent which son or daughter is their favorite. In 2013, the Mineralogical Record published an Arizona Collector’s Supplement. I was honored to be included. Several of my specimens were photographed for that issue and some of them are shown in this article.

Some favorites would include a 2.8 cm group of dioptase included in calcite rhombs from the Tsumeb mine, Namibia; a “killer” 2.5 cm cubanite twin from the Henderson No 2. Mine, Chibougamau, Quebec, Canada; a fire-red 2.5 cm transparent rhondonite from the San Martin mine, Chiuricu, Huallanca, Ancash Department, Peru; and, a 3.1 cm single veszelyite crystal from the Black Pine mine, Phillipsburg, Montana.

TP: Recently you and Laura moved to Tucson, Arizona – the mineral collectors’ Mecca – and you immediately got involved in exhibitions, collectors meetings etc. You’ve also had the opportunity to collect in some of the mines in the Tucson area. Can you tell us more about this most recent chapter of your collecting history? What are your plans for the future?

AS: Talk about busy, since moving to Arizona. One of the first contributions was to work with Jim Houran on displaying a collection of Chinese thumbnail specimens as part of a Special Exhibit of Chinese Minerals at the University of Arizona’s mineral museum.

As soon as we moved to Tucson we joined the Tucson Gem and Mineral Society (which manages the TGMS Show each year). We were invited to join the Arizona Mineral Minions group, and the Mineral Enthusiasts of the Tucson Area (META) group. It has been a great pleasure to meet many of the Mineral Minions and META members throughout the state and to see their collections. We’ve been attending monthly meetings of TGMS during which time many superb presentations have been given on mineralogy. I’ve also had a chance to meet many miners around the state now in their 70s and 80s, and listen to fascinating stories about their experiences working in the mining industry, and as collectors. Some have impressive mineral collections acquired over a lifetime.

Mineralogy has given so much to me during my life that finding ways to give something back is important. In 2014, I was elected Vice President of Friends of Mineralogy (FM), a group every mineral enthusiast should join, with chapters throughout the United States. These chapters put on regional shows, and organize outstanding educational events, exhibits and socials. FM promotes, supports, protects and expands the collecting of mineral specimens and furthers the recognition of the scientific, economic and aesthetic value of minerals and mineral collections. If elected as president in 2015, I hope to do my part in further promoting the organization’s objectives. This year we will be working more closely with Mindat.com to optimize its benefits for the mineralogical community.

It did not take me long after arriving in Arizona to get my hard hat on and head underground. I have MSHA (Mine Safety and Health Administration) certification, which allows me to go underground to collect specimens when invited, or simply help out other miners and collectors with mucking-out or with safety issues. The most recent visits have been to the Rowley Mine in Maricopa County, which recently located the world-class wulfenites with 1.0-1.5 cm fire-red mimetite balls that were available at the 2014 TGMS show. I’ll probably be digging for specimens at mine dumps around the state and visiting mines in Colorado, New Mexico, and Nevada over the next few years.

Jim Houran, a fellow thumbnail collector, inspired me to continue the tradition he started with Rich Olsen to promote thumbnail collecting. It has been a delight to work with both of them and other collectors to create invited theme exhibits focusing on thumbnails displayed at major mineral shows such as Munich and Tucson.

TP: We wish you many more collecting adventures as well as many new small specimens for your collection!