F. John Barlow Collection: A Modern Mineral Connoisseur

Within the mineral collecting world, there are collectors who have left their indelible mark upon the community. John Barlow was one of those collectors. This article does not aim to give you a chronological take on his life here. Others have done that. Instead, this article examines how Barlow was a trailblazer of modern mineral connoisseurship and what we can learn from that. He is an example of the many collectors who assembled a significant collection and then took the time and effort to share (through his book in 1998; as well as many exhibitions). Primarily this seeks to examine his collecting philosophy and how it helped him to gather his Great collection.

There is something poetic in the parallels seen in his life and his mineral collecting.

Barlow was born at the beginning of the 20th century and passed away at the beginning of the 21st century (1914-2004). During his 90 years, he witnessed dramatic shifts in American life. Barlow witnessed dramatic shifts in the American social, political, and physical landscape. His endless curiosity, hard-working ethic, seemingly boundless energy, and entrepreneurial spirit made it possible for Barlow to succeed in business and then he applied the same energy to "hunting" minerals, as he called it. He always talked about mineral collecting as a sport, not a hobby, and felt that showed more energy and passion.

From an early age, Barlow was a businessman. At age 12 he established the “Sunset Stamp Company”: first collecting stamps, then selling stamps, then buying stamps to sell stamps. A tactic he would use again in the future. His instinct for business would serve him well over his lifetime. It aided him in his pursuit of his Mechanical Engineering major and Business minor stress the University of Washington during the Great Depression, or transitioning from an engineer to becoming the #3 man at Western Condensing Company during World War II. Later he founded AZCO, A-Z Engineering Corporation. Starting with $5,000 in seed money, he would become one of the largest mechanical contractors in the US and some people say he built half of Wisconsin and a number of airports. However, Earth Resources - his mineral, gems, and jewelry company- was always one of his favorite projects.

Barlow began collecting at the beginning of the 1970s. His voracious curiosity was peaked by an Amethyst geode from the Atlas Mountains of Morocco given to him by his daughter Grace. This piece began a 30+ year love of mineral collecting. When Barlow did something, he DID something. In a similar fashion to how he picked up flying, then proceeded to use it as a regular mode of transportation (this man would fly a plane across the country to see a rock back when others waited until the next show!). He went “all in” with mineral collecting.

Truly fabulous collections are a reflection of their collectors. A collector’s “eye,” what attracts a collector to particular aspects of a mineral, results in a distinct aesthetic...Something that brings the ensemble together. Barlow was fascinated by collecting philosophy; he even had Bob Jones write a chapter on the “collector’s instinct” in The F. John Barlow Mineral Collection. Collectors are “hunters"; always looking for the next deal, the next great piece, the next elusive specimen...

Barlow was a collector’s collector.

He pursued specimens of all types: the rarities, the scientifically interesting, the beautiful, the elusive, the entire pocket, and the pieces he just liked gosh darn it. Barlows collection encompassed over 6,000+ specimens (not counting many duplicates and the rares and systematics - so perhaps the true total was double that). His collection was “deep,” and he was not satisfied with acquiring the minerals... he studied them. And then he went out and shared what he learned, which makes sense coming from a former Sunday School teacher! He participated in exhibitions at museums, schools, and mineral shows. Because he collected across the spectrum of size and price and rarity, he literally could patronize any dealer and talk with any collector as a peer.

He was also incredibly competitive, whether marbles as a child, football in high school and college, or as a businessman. Early on, he entered a competitive mineral display case. He lost. Being Barlow, he then directed his considerable energy and resources into acquiring the Best available AND making custom plastic stands with engraved labels at a time when nobody did so. He went on to win the Ed McDole Memorial Trophy in 1975 and again in 1978. In 1993 he returned to win the Paul Desautels Trophy (which replaced the McDole). That same year his Sperrylite won the Walt Lidstrom Memorial Award. His highest honor, the Carnegie Mineralogical Award, was awarded in 2000.

Barlow was not content to be told what was “good." Instead, he did his research — contacting museums, other collectors, and even dealers to find out how good a particular find got. For example, after encountering small Red Beryl crystals from the Wah Wah Mountains of Utah, Barlow contacted the Smithsonian. They had a 1.6 x 1.1 cm example, which was considered the best at the time. So he felt satisfied acquiring #2 but always kept his eyes peeled for better. According to mineral collecting lore, he got his chance during the Tucson Show, back in the day where circuit breakers regularly overloaded from all the display lights in dealer's rooms. So while the lights were flickering on and off, he was shown a flat of material from the Harris Mine. Barlow believed that he was looking at the best Red Beryls to ever come out, despite the atrocious lighting. And he was right! He bought them all and assembled the best known suite ever of red beryl.

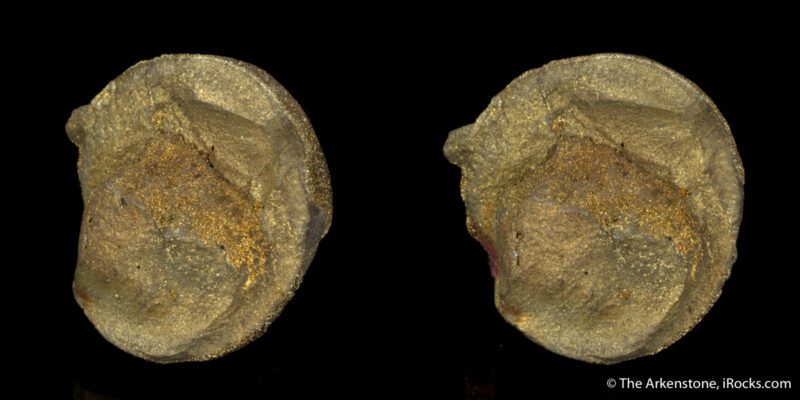

[caption id="attachment_6365" align="aligncenter" width="533"] Red Beryl; Harris Claim, Wah Wah Mountains, Utah. This specimen is one of the pieces Barlow acquired that night. It is a truly stunning example of the material and arguably the best. Barlow had a soft spot for this material; he even went there collecting himself! This particular was one of his favorites! 6cm. Joe Budd Photo[/caption]

Red Beryl; Harris Claim, Wah Wah Mountains, Utah. This specimen is one of the pieces Barlow acquired that night. It is a truly stunning example of the material and arguably the best. Barlow had a soft spot for this material; he even went there collecting himself! This particular was one of his favorites! 6cm. Joe Budd Photo[/caption]

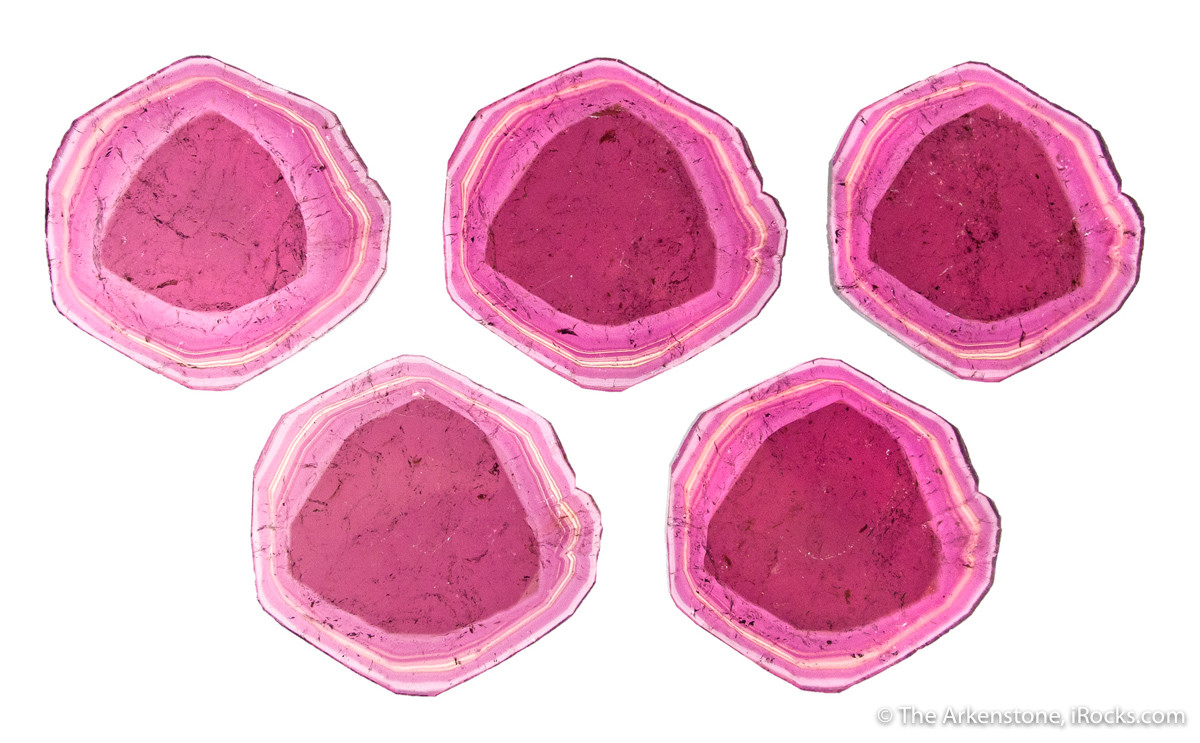

One remarkable aspect of Barlow’s collection were the suites. Where most collectors of his caliber focus solely on the exceptional, Barlow wanted his Collection to be outstanding as a whole group of "Suites of Suites"! His Mexican suite is an excellent example. While flying down to Mexico for fishing trips, Barlow began collecting minerals from south of the border. There were some great pieces, namely some fantastic Silver sulfide minerals, which were also a part of one of his other suites (silver species, which was near completion). Barlow had 468 Mexican minerals in his Collection. Remarkably, 266 of these were mini-suites of single species from single localities. He had 11 Rhodochrosites from Santa Eulalia, 21 Ludlamites also from Santa Eulalia, 25 Legrandites from Ojuela, 46 Adamites from Ojuela, 50 Boleites from Boleo (some of which he self-collected, and 77 Purple Creedites from Santa Eulalia! Barlow accumulated these by buying entire lots representing a particular find or, in some cases, entire pockets! Barlow’s habit of doing this resulted in a comprehensive representation of the many different habits, associations, and styles from a similar or shared genetic source. So this suite was both aesthetically important, but also scientifically as well.

[caption id="attachment_6363" align="aligncenter" width="533"] Vivianite from the 13th level, San Antonio Mine, East Camp, Santa Eulalia District, Chihuahua, Mexico. Formerly in the John Barlow Collection (illustrated in his book from 1998, on page 340), it was sold off in 1998 along with the rest of the collection and quickly nabbed by Arizona/Mexico collector Evan Jones. Evan sold the Mexico suite to concentrate on Arizona, and at that time I purchased this piece for the Stoudt collection. Joe Budd photos.[/caption]

Vivianite from the 13th level, San Antonio Mine, East Camp, Santa Eulalia District, Chihuahua, Mexico. Formerly in the John Barlow Collection (illustrated in his book from 1998, on page 340), it was sold off in 1998 along with the rest of the collection and quickly nabbed by Arizona/Mexico collector Evan Jones. Evan sold the Mexico suite to concentrate on Arizona, and at that time I purchased this piece for the Stoudt collection. Joe Budd photos.[/caption]

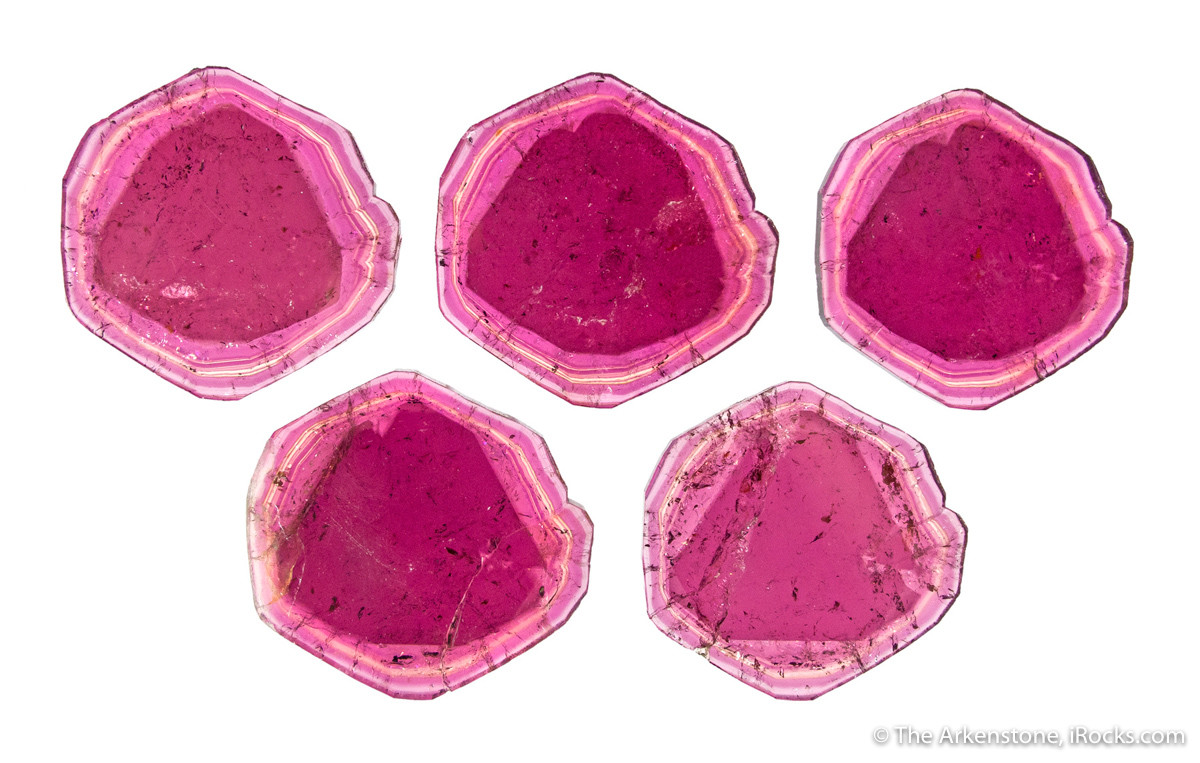

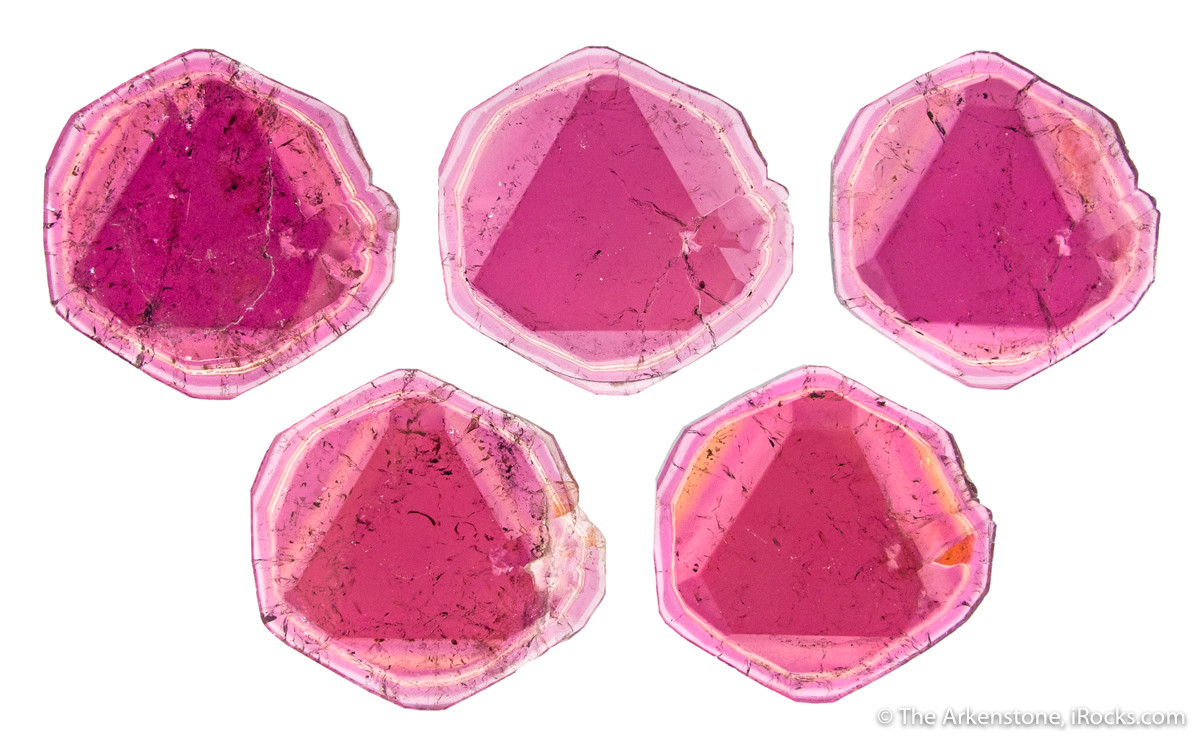

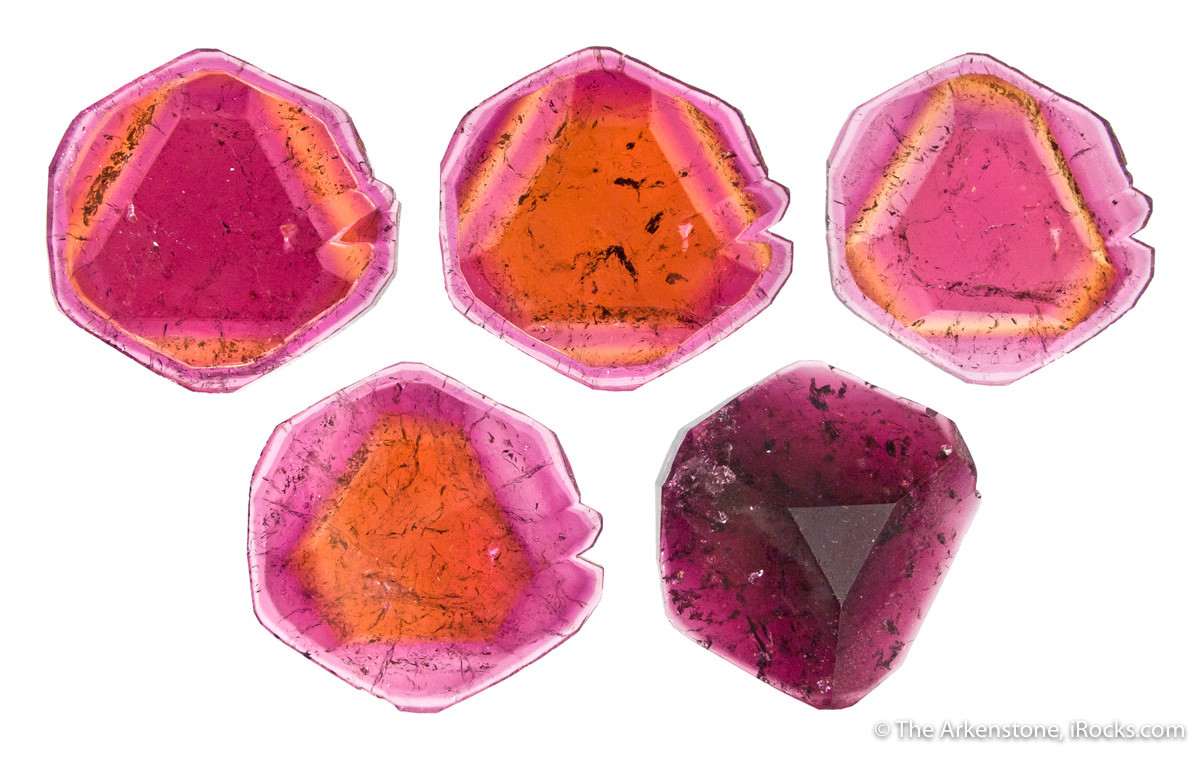

While Barlow primarily collected with a silver-pick, he also took the opportunity to use a rock pick. He collected personally in Boleo, the Wah Wahs, and even in the Queen and Himalaya Mines in San Diego. During his underground excursion at the Tourmaline Queen, he realized that it would be incredible to share what a pocket looked like with those who didn’t have an opportunity like this. So after collecting a couple of crystals himself, Barlow had the entire pocket, feldspars, quartz, essentially the pocket wall, quartz extracted and later reassembled.

[caption id="attachment_6366" align="aligncenter" width="800"] This pair of Creedites are both from the Pinata Orebody, West Camp, Santa Eulalia, Chihuahua, Mexico. Barlow systemically bought a considerable percentage of the specimens that came out from 1982-1984, exemplifying how this collecting style captured the breadth of styles coming from this zone.[/caption]

This pair of Creedites are both from the Pinata Orebody, West Camp, Santa Eulalia, Chihuahua, Mexico. Barlow systemically bought a considerable percentage of the specimens that came out from 1982-1984, exemplifying how this collecting style captured the breadth of styles coming from this zone.[/caption]

Barlow’s life’s story really comes together when we look at a specimen known as the Postage Stamp, his pride and joy and the cover image of his Book. Afterall, Barlow had his start in business selling stamps, and this Tourmaline Queen Elbaite with Quartz became one of his dearest pieces. The piece was one of four specimens featured on a U.S. postage stamp in 1974. After a long chase, Barlow finally acquired the specimen in 1983. It was the specimen that he selected as the cover of his book, and the inner cover is decorated with images of the first issue of the stamp.

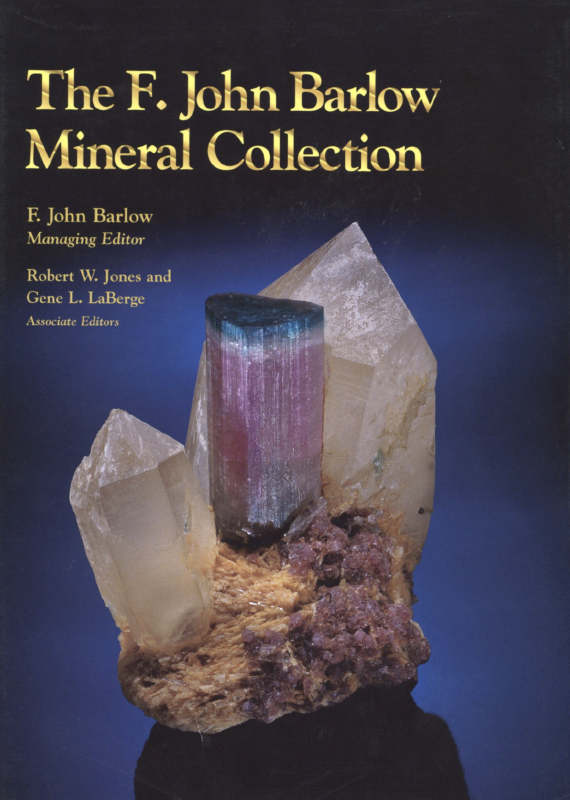

One of Barlow’s most significant achievements was The F. John Barlow Mineral Collection book. The book mirrors the man’s magnificent collection and educates and inspires through the sheer breadth of it. It is still relevant today, over 20 years later... dive into the combination of collecting philosophy, history, photos of his fantastic examples from different finds, researched provenance explained through easily accessible stories. The book stands as one of the best books to read at the beginning of one’s collecting career.

One of Barlow’s most significant achievements was The F. John Barlow Mineral Collection book. The book mirrors the man’s magnificent collection and educates and inspires through the sheer breadth of it. It is still relevant today, over 20 years later... dive into the combination of collecting philosophy, history, photos of his fantastic examples from different finds, researched provenance explained through easily accessible stories. The book stands as one of the best books to read at the beginning of one’s collecting career.

He was an engineer. An intrepid adventurer. A family man. A lifelong student. A meticulous researcher. In general, an energetic and curious man, who in many ways does an incredible job of encapsulating the characteristics of a “true” collector.

The Arkenstone bought Barlow’s thumbnail collection and a large part of his rare species suite in 1998 -99. The majority of his collection was sold to a consortium representing the Houston Museum, which got many of the best pieces and consigned the rest out through a prominent dealer. Thousands of pieces found new homes, and they occasionally turn up again today. It is always fun to go look in his book and see if any of the illustrated pieces are on the market again. Several from the collection are now available, on our website as well!

Sources:

Barlow, F. John, et al. The F. John Barlow Mineral Collection. Sanco Pub., 1996.

WILSON, W. E. (2004) Obituary--F. John Barlow. Mineralogical Record, 35, 362-363.

18.7 cm, from the San Juan Poniente stope, Level 5, of the Ojuela mine, Mapimí, Durango, Mexico. “The Aztec Sun,” Jeff Scovil photo.[/caption]

18.7 cm, from the San Juan Poniente stope, Level 5, of the Ojuela mine, Mapimí, Durango, Mexico. “The Aztec Sun,” Jeff Scovil photo.[/caption] Miguel Romero in 1992, at his home in Tehuacan, showing the “Aztec Sun” legrandite, his most famous specimen, to Texas collector Imelda Klein in 1992.[/caption]

Miguel Romero in 1992, at his home in Tehuacan, showing the “Aztec Sun” legrandite, his most famous specimen, to Texas collector Imelda Klein in 1992.[/caption] 5-cm view, from the Nevada mine, Batopilas, Chihuahua, Mexico. Ex. Romero collection. Joe Budd photo.[/caption]

5-cm view, from the Nevada mine, Batopilas, Chihuahua, Mexico. Ex. Romero collection. Joe Budd photo.[/caption] Read the Mineralogical Record supplement featuring Dr. Miguel Romero's collection online!

Read the Mineralogical Record supplement featuring Dr. Miguel Romero's collection online!

Cut emeralds from recent finds in Ethiopia[/caption]

Cut emeralds from recent finds in Ethiopia[/caption]

A beautiful Tanzanite ( variety of zoisite) Rough crystal and cut gem. Both are from Tanzania.[/caption]

A beautiful Tanzanite ( variety of zoisite) Rough crystal and cut gem. Both are from Tanzania.[/caption]

One of the finest red beryl specimens. 6cm tall.[/caption]

One of the finest red beryl specimens. 6cm tall.[/caption] Benitoite crystal from Dallas Gem Mine area in San Benito, California. Copyright The Arkenstone, Joe Budd Photo.[/caption]

Benitoite crystal from Dallas Gem Mine area in San Benito, California. Copyright The Arkenstone, Joe Budd Photo.[/caption] Peter Bancroft authored Gem and Crystal Treasures, detailing 100 of the world's top mineral localities.[/caption]

Peter Bancroft authored Gem and Crystal Treasures, detailing 100 of the world's top mineral localities.[/caption] Lustrous cut Benitoite gemstone from the Dallas Gem Mine.[/caption]

Lustrous cut Benitoite gemstone from the Dallas Gem Mine.[/caption]

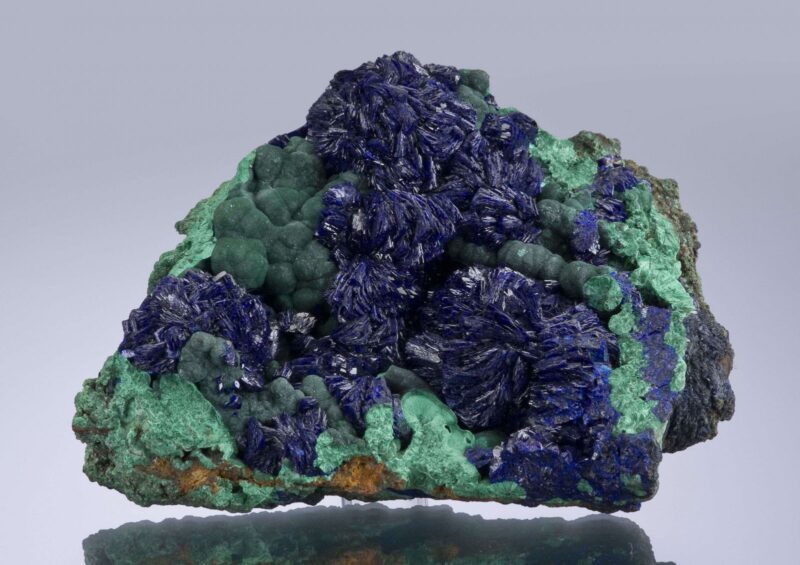

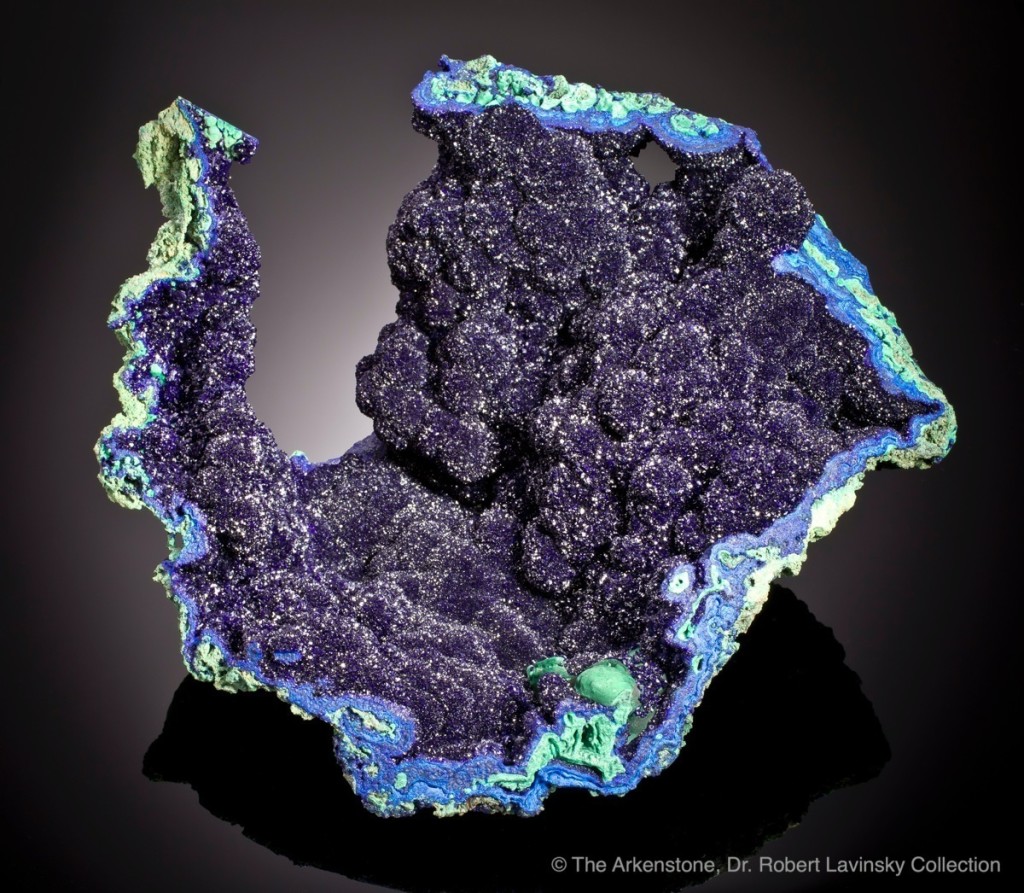

A shimmering azurite specimen from Anhui, China is an impressive 29cm tall. Joe Budd Photo.[/caption]

A shimmering azurite specimen from Anhui, China is an impressive 29cm tall. Joe Budd Photo.[/caption] A Tsumeb Mine Azurite caught exactly halfway in the pseudomorphing process! This is the same process that causes the Azurite pigments to fade to green .[/caption]

A Tsumeb Mine Azurite caught exactly halfway in the pseudomorphing process! This is the same process that causes the Azurite pigments to fade to green .[/caption]

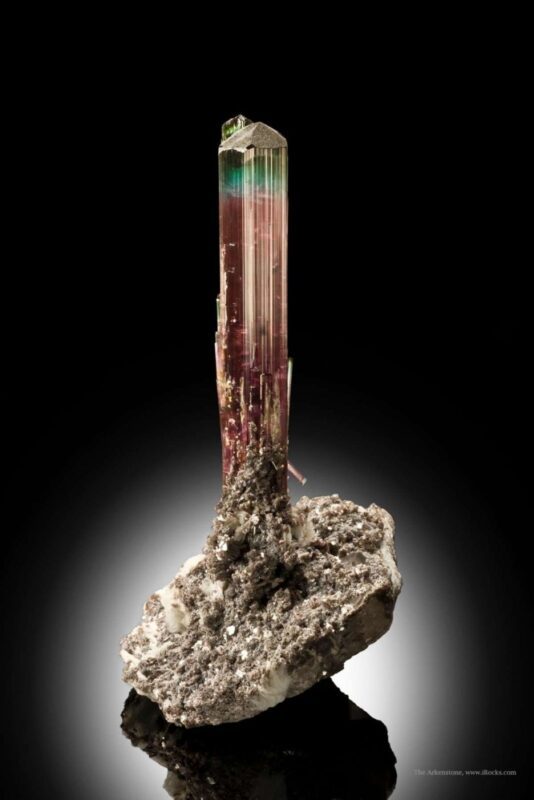

Exceptional 31 cm tall Multi-colored Elbaite Tourmaline from Pederneira Mine, Minas Gerais, Brazil.[/caption]

Exceptional 31 cm tall Multi-colored Elbaite Tourmaline from Pederneira Mine, Minas Gerais, Brazil.[/caption]

At the Arkenstone Gallery, fine minerals fill custom-built lit cubbies with bright pops of color.[/caption]

At the Arkenstone Gallery, fine minerals fill custom-built lit cubbies with bright pops of color.[/caption]