Competing with Thumbnails: Little Crystals, Big Impact

By David Tibbits

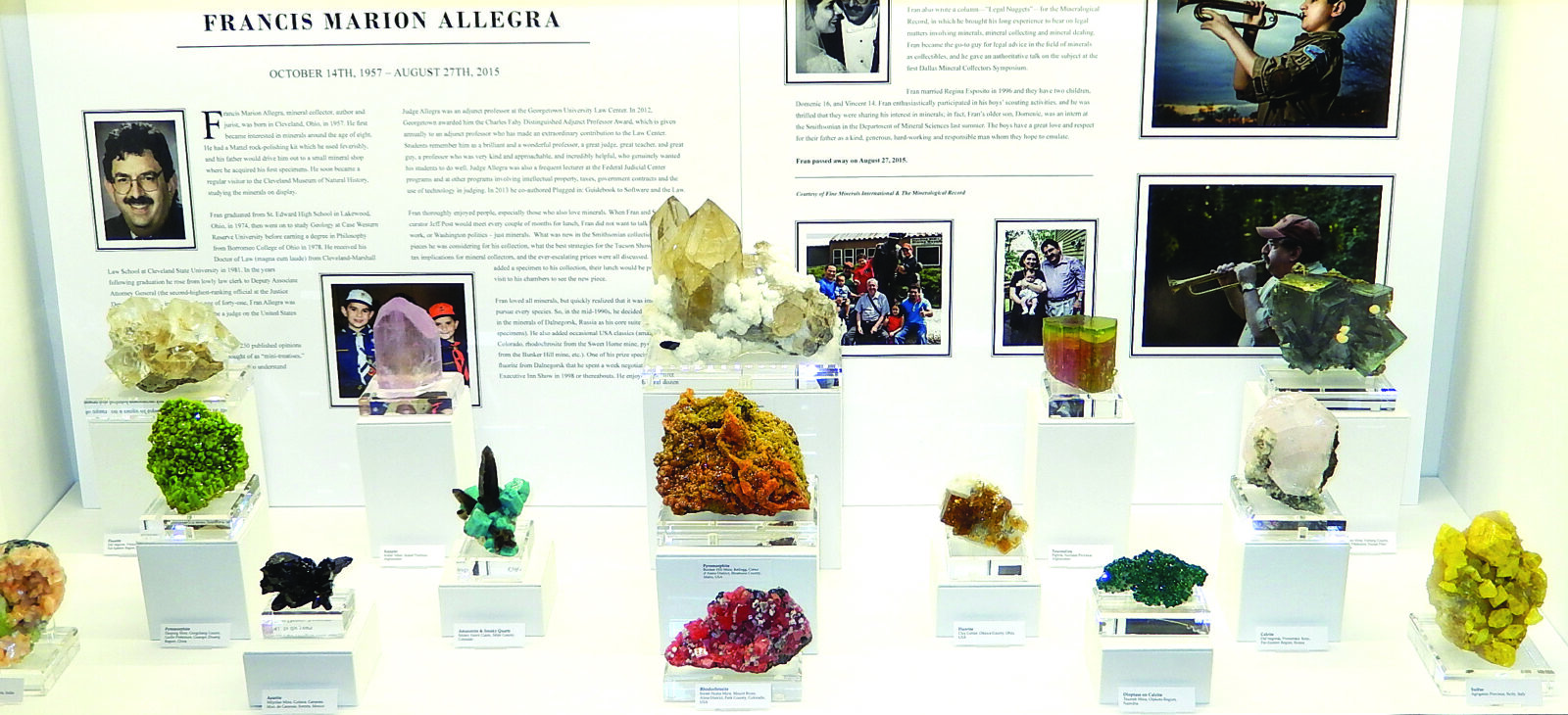

Over the years, many generations of mineral collectors have participated in mineral competitions at the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show. This year was no exception, as folks of all ages with different experiences in collecting and collecting interests populated the 2022 TGMS with a large section of competition exhibits. To those who spend hours looking over every case exhibited at the convention center, the competition sections offer a look at the highest quality each collector exhibiting has to offer. I have heard all sorts of questions about mineral competition ever since I put in my first competition display: What even is a mineral competition? How do you determine a winner? What makes a mineral ‘competition worthy’? Usually, after hearing the answer to these sorts of questions, the following question I receive is “How can I sign up?” My goal is to help answer some of these questions throughout this article, and hopefully inspire you to consider competing one day.

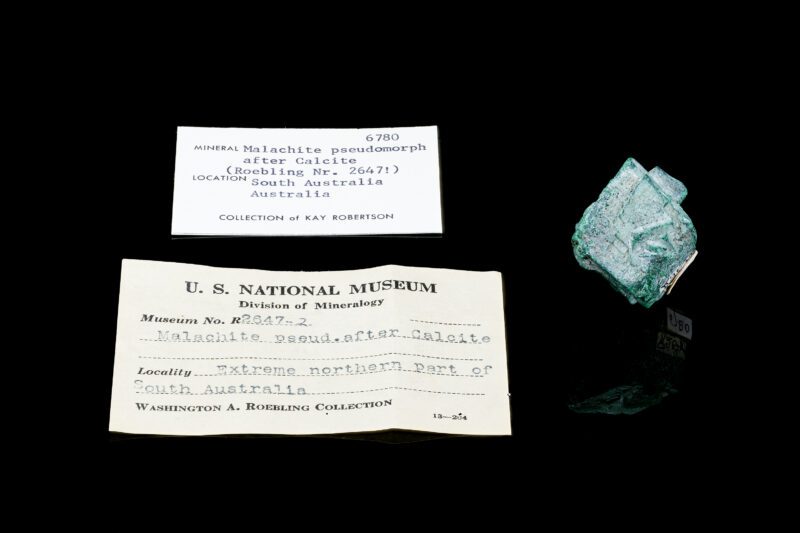

At the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show, there are various categories for competition, each divided into five skill levels. Just about any classification of collecting imaginable exists as a category for competition. I have personally competed in the thumbnail size class as well as self-collected minerals and single locality minerals. Other categories include things like single crystals, pseudomorphs, single species, mineral families, or mineral groups. For the most part, the only things required to put in a competition display are: the minerals, labels for the minerals, liners for the walls of the wooden cases, and risers to arrange the minerals on top of. Essentially, an exhibitor is assembling a museum quality exhibit with their selected specimens, and will want everything to be perfect. Competitors are judged upon four criteria: quality of specimens, showmanship of their display, accuracy of labeling, and the rarity of the pieces. Assembling high quality labels, liners, and risers is relatively straightforward, however selecting which minerals to compete with is the most difficult and confusing part. After all, how can we expect perfection of minerals, when we ourselves have no role in their creation?

To discuss what aspects of a mineral can make it ‘competition worthy,’ I will be focusing on thumbnail minerals in particular, as that is the category for which I have the most experience, typically interests the most people, and requires the highest number of specimens as a minimum for entry. After all, thumbnail mineral competition has had the longest legacy, with its origin dating back to Arthur Flagg who organized the first thumbnail competition at the Arizona State Fair sometime around the 1940-50s. Of course, the principles of quality in thumbnails scales up to any other size class of mineral.

In order to judge a mineral's quality, a team of three judges each assigns every mineral specimen a score from 1-10, and then the average of these scores makes up the points for the quality section overall. For most levels, quality makes up 75 points of the overall score. Take for example, an exhibit scoring an 8.5 average quality amongst its pieces would contribute 63.75 points to the overall score. According to the TGMS Competitive Exhibitor Handbook, the criterion on which mineral quality is judged is:

- Judging will be based on the condition of crystals (freedom from bruises and flaws); size of crystals (typical of species); color (typical or exceptional for the species); aesthetics (arrangement of crystals); clarity (freedom from excess foreign material); and the visible amount of identified mineral(s) to be judged.

Summed up, a mineral’s quality is based upon every possible quality that mineral may possess, which unsurprisingly can be quite subjective. Something important to keep in mind is that each piece is judged upon its quality versus all other localities and varieties that do exist. That is to say, all beryls are judged against each other, all wulfenites are judged against each other, and all calcites are judged against each other. In many cases, a particular specimen can be exemplary given the material at its locality, but merely adequate in comparison to another find.

Another important thing to consider is that for a specimen, only one mineral species present can be evaluated. You will need to specify via label which species in a combo you’d like to have judged by putting it in all caps. Ultimately, in order to receive scores of 10s, a specimen needs to be the best of its species. That is, the best that has ever been seen, both in private hands, museums, or universities. Since acquiring pieces that are the best of species can be incredibly hard, you will need to study what the best can be and attempt to emulate those features.

With all of that being said, there are some general guidelines which can be used to determine if a mineral is competition worthy. The highest quality single crystal thumbnail minerals often reach the 1” maximum size, as anything smaller than 1” can mean that larger pieces exist. However, there are instances where this may not be the case, such as certain species that are not known to achieve this larger size, or when larger specimens negatively impact aesthetics, transparency, color, etc. So, while size is a big factor in selecting competition-grade specimens, it should be considered as part of the whole picture.

Visible damage is inevitably a negative penalty, since that same piece damage free is always better. Sprays and combinations tend to do worse than single crystals, except in the cases where the species only exists as sprays, or alongside other minerals. This means that for your typical mineral species, you will want to look for damage-free large crystals which exhibit nice color, luster, and aesthetic. Many competition thumbnail cases feature vanadinites from Morocco, pyrites from Spain, sulphohalites from California, and fluorites from various localities, as these species/localities yield tons of thumbnails that meet the requirements for good scoring, and don’t break the bank. Over time, as you become more familiar with what exists and what is possible, your eye for quality will improve.

Personally, my highest scoring piece is my bixbyite with topaz from Thomas Range, Utah. It's not hard to see why, as it is enormous for its species, and the tiny topaz on its backside adds a great aesthetic flair.

An example of a great scoring piece that's not in my collection is this danalite from New Hampshire. Danalite is a mineral most people are unfamiliar with, and comparing to other specimens online, particularly on mindat, you can see how this piece stands far apart from the rest of its species. It is incredibly well formed and sharp, combined with characteristic color and a size pushing the boundaries of the thumbnail class. It is no surprise that this piece scored an average of 9.75 when it was in Brandy Naugle’s competition exhibits at both the 2011 and 2013 TGMS.

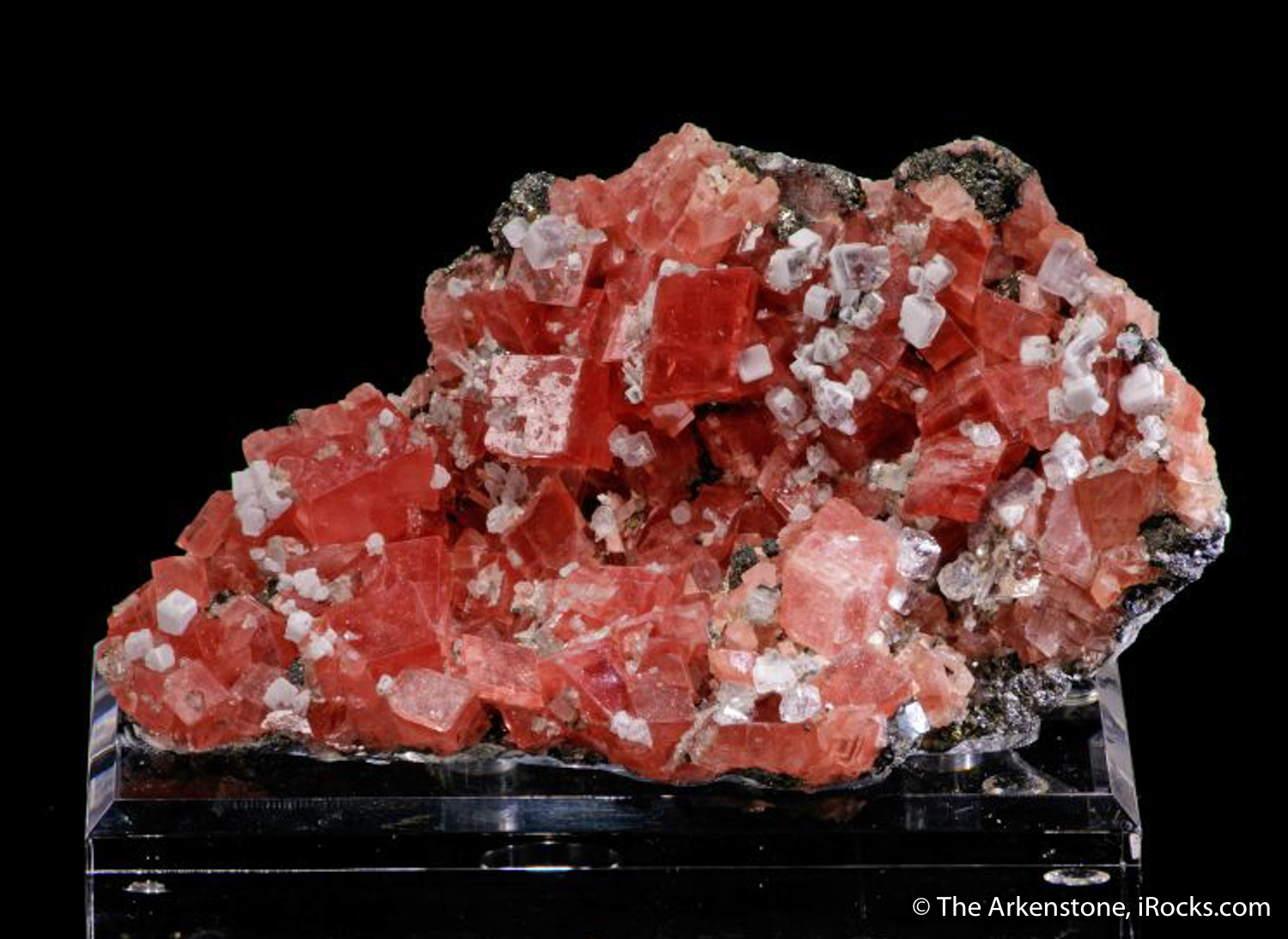

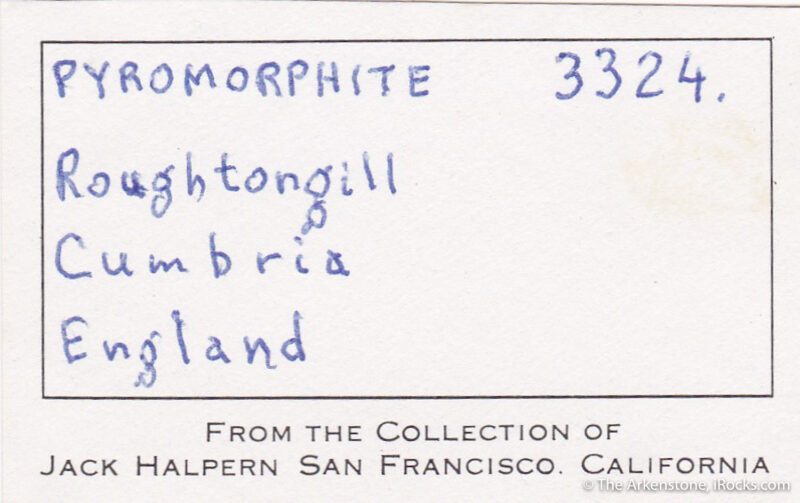

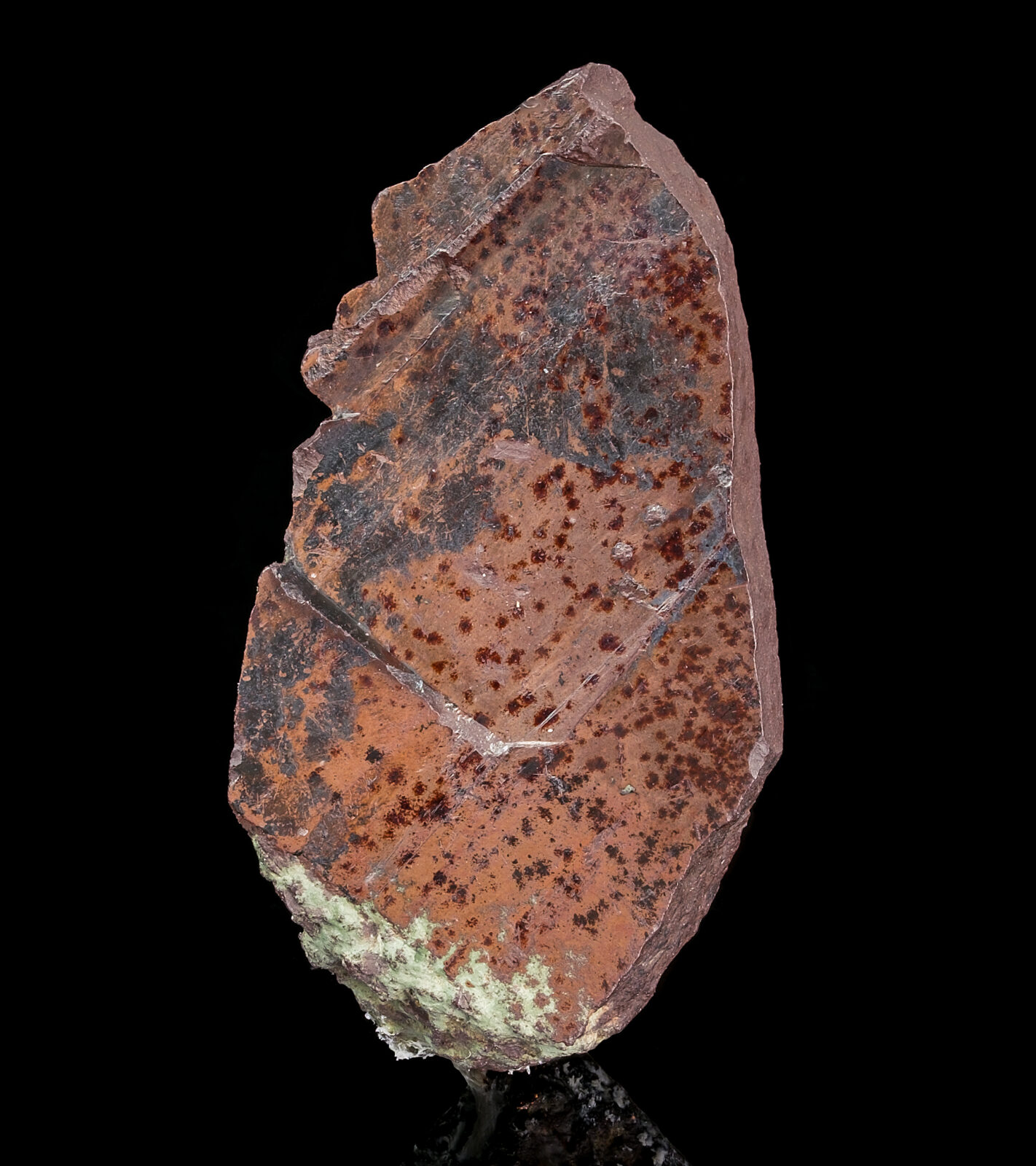

A few great specimens available for sale on iRocks now and previously are:

This particular demantoid is incredibly competition worthy. At 2.5cm it fills in the 1” requirement, and with a brilliant translucent green color, it stands far above the typical garnet that you would expect. It is worth noting however, that the provenance of the specimen previously being in Dr. Federico Pezzotta’s collection does not increase its value to competition as the judges would not be aware of this, however it certainly does contribute to the value of the piece.

Speaking of Dr. Pezzotta, this pezzottaite approaches perfection for the species. Pezzottaite is one of those rare minerals that does not come from a lot of places, and you don’t see too many examples of on the market. Many pezzottaites are not complete on all 6 sides, or are heavily etched out on their ‘front’ face. This specimen is the ideal when it comes to form and color, and the fact that it is 2.3 cm in width means that the only way to improve the specimen for competition would be to increase its size by 2 millimeters.

Here is an example of a competition worthy thumbnail which ‘exceeds’ the 2.54cm size limit. Standing vertically, this thumbnail is 2.9cm in height, so this crystal of vesuvianite would need to be tipped back in order to fit the required dimensions for a thumbnail on display. Its sharp form and great green color makes it nearly ideal for the species of vesuvianite. It is possible that a judge may find himself partial to the purple vesuvianites available from the Jeffrey Mine in Canada. This might mean that this piece would only be very high scoring instead of approaching a 10.

It's not hard to see how these could score quite well. There definitely is a common theme that connects them. Exemplary color and form, combined with a large size.

On the other hand, it is often that a piece you absolutely adore scores not quite so perfectly. An example of this, from my experience, is this fluorapatite from Golconda Mine, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Although it has great color, aesthetics, clarity, and pushes the limit of size, it struggled to break even the 8 point threshold with this piece. That is because even though the piece is very nice, the individual crystals which make up the specimen are very small for apatite. This stands in contrast to another fluorapatite in my collection, which has a similar color and size, but has much larger crystals.

In the end, scoring still can be quite subjective. Even on a year to year basis the scores of a single specimen can change, based on judges or the other specimens submitted for judging that year. You might think you have a total 10, until you see another piece in someone else’s display that feels like an 11!

JUNIOR COMPETITION

Several competitions also have their own separate categories for younger collectors, such as TGMS’s Junior and Junior Master divisions, for 8-18 year olds. Dr. Rob Lavinsky has always been a passionate supporter of young collectors, as he himself was lucky enough to have several notable mentors when he was just in his young teens. Each junior age exhibitor, regardless of which exhibitor class they enter, will receive a $100 check from him, the high point score by a junior-age exhibitor receives $500, and the second-high point score will receive a $300 check, as a way of honoring those who helped him when he was a young collector.

With a greater perspective of what makes for a competition grade mineral, I highly encourage you to get involved in competition, regardless of whether or not you think you have enough high quality minerals. There is so much to gain, even just from being a part of the process. Competition requires you to become very familiar with the pieces you own, leading you down a path of intense research. You will have no choice but to research the localities of the pieces to ensure their accuracy in labeling.

Another added benefit is a connection to the community of competitors, which in my experience have always been welcoming and supportive, rather than toxic and cutthroat as other sorts of competition sometimes lend towards. And ultimately, the greatest benefit to competition is that you get an outlet to display your specimens to the public. This builds provenance for your collection as a whole as well as the pieces as individuals, and gives you the opportunity to share the pieces you love with friends and strangers alike.

If I have convinced you to consider competing with thumbnails, here are some next steps:

Pick a category and read the rules.

Build the display and create the labels.

Around fall/winter, signup becomes available on the TGMS website.

There are a few clubs which heavily promote competition like the Mineralogical Society of Arizona, or the Flagg Mineral Foundation which you might consider joining, even remotely.

If you are below the age of 40, I’d recommend joining the Young Mineral Collector’s Facebook group to connect directly with other mineral competitors.

More info still can be found in this article by Les Presmyk and Marc Countiss, which offers a greater perspective into competition as a whole, as well as includes a ton of great photos, beyond what is featured in this article.

If all of those options for learning more still aren’t enough, you can feel more than welcome to reach out to me, other collectors, or staff members at The Arkenstone, as there’s a wide group of people happy to talk minerals!

We'd like to thank our friend, Young Mineral Collector's member and award-winning competitor David Tibbits for graciously authoring this article.